Martha's story

Poetry - "Break In Silence"

Art - "Self-Sabotage"

Advice from a therapist

Worksheets

Transcripts

Who to call for help

Understanding self-harm

Martha's story

Martha's Story

Martha Binkley is very open about having a mental health condition, but she says that does not define who she is. For Mosaics she wrote an essay about living with a condition and created a series of self portraits. These images are rough drafts. Her story is the first in the podcast.

Societies, Involvement, and Improvement

By Martha Binkley

All mental health can be quite consequential, and also at times detrimental to not just one’s well-being, but also their state of mind. And also their own physical health. You could note that one truly should try and trade all the wealth in the whole wide world for any kind of real happiness.

It can be relentless, more than just overwhelming when dealing with your own mental stability, ultimately, eventually, it can be exceptionally difficult, in fact, sometimes hopeless.

Especially if one becomes homeless, but eventually, hopefully, mostly there are those who do prevail and maybe not, overcome or even cure for sure their disease, disability, or even disorders. Not accepting or letting them become so-called “disadvantages.” Rather, like passages in life, stepping stones, tools in life. As a person individually descends and crosses through the “linear space,” the “threshold.”

Possibly, not just overcoming and striving and hopefully not dying at the hands of another, but also not by their own hand, believing they’re worth less than someone “Normal” taking their own self-worth for granted.

It not only depends on the person but those around them, family and friends, people in society. But ultimately, 50 percent is their own environment. Living, existing is, to me, one of life’s requirements.

All it takes is someone just willing to be the one just listening. It can be a mental breakdown happening unwittingly, ultimately at any given time, even if one’s in their prime...there’s a variety of factors including not at all limited to one’s “genes,” all that they’re inherited throughout their own lineage.

It’s unpredictable like Mother Nature’s unknown almost deadly silent “Revenge.” an unforeseen lifelong battle, a war that rages from within one’s “psyche.” They’re intelligent, their mind their own brain, turning against themselves. Thinking and seeing even your own flesh and blood, friends, family, and innocent people as the ENEMY! It can in a sense, for instance, be overcome. But the damage may never be undone.

I believe EVEN when one’s mind may deceive themselves when one receives more than just support and also therapeutic tools and also therapy they’re somewhat accepted and also newly learned coping skills is part of some sort of humanity’s recovery process.

In all of our own communities, spreading and teaching all others that the Normal stereotypical stigmata with “Mental Illness” assumptions that they, the sick person, must be crazy or have “schizophrenia,” not just influences one’s mania and or paranoid delusions, but is and can be detrimental to the person as in their whole well-being.

Seeing that [through] their own eyes, being empathetic and being sympathetic, is more than therapeutic, more than just understanding. It’s, well, that moment, mentally, that can change one’s life, and impact influence on one’s path, their life, for the better.

Soon, I hope and pray, one day also I wish it won’t be so strange. But become the “Normal.” Accepting, not letting one become a casualty of a relentless, ruthless war Mental Illness, Disorders, Disabilities, I believe are, Misunderstood.

Losing sight of our individual abilities creates our own instabilities. But in our societies without education, there’s more than just a hesitation dealing with such diagnoses leading to society’s prognoses that they're unwanted, incapable of being equal.

It's like a child’s inescapable worst night terror, society’s own, endless nightmare to compare their normal with another deprives our own understanding and comprehension and only describes humanity as a whole as born naive, moronic, retarded “stunting our growth.”

Our only reprieve is that we can no longer pretend like everything is acceptable, keeping another person down. With learning and experience comes wisdom. When an individual person loses their humility, they’ve all but lost their own humanity, and also their own morals.

Acceptance and understanding irrevocably are not just influential but consequential, not at all coincidental, in enhancing, not changing, improving one’s development. Advancing them and others. Not just glancing back, enhancing one’s life for the better.

Along with many and all cultures, a great many peoples and all walks of life, tribes and also individuals in all societies: Changing society’s preconceived nations will invoke emotions but revoke even Nations of Peoples taught generally untrue prejudgments of Mental Health.

One day, we can all say we’ve fought and not forgotten how rotten people used to treat each other. It’ll become, I do believe, more than just a dream, and also a movement.

By Martha Binkley

All mental health can be quite consequential, and also at times detrimental to not just one’s well-being, but also their state of mind. And also their own physical health. You could note that one truly should try and trade all the wealth in the whole wide world for any kind of real happiness.

It can be relentless, more than just overwhelming when dealing with your own mental stability, ultimately, eventually, it can be exceptionally difficult, in fact, sometimes hopeless.

Especially if one becomes homeless, but eventually, hopefully, mostly there are those who do prevail and maybe not, overcome or even cure for sure their disease, disability, or even disorders. Not accepting or letting them become so-called “disadvantages.” Rather, like passages in life, stepping stones, tools in life. As a person individually descends and crosses through the “linear space,” the “threshold.”

Possibly, not just overcoming and striving and hopefully not dying at the hands of another, but also not by their own hand, believing they’re worth less than someone “Normal” taking their own self-worth for granted.

It not only depends on the person but those around them, family and friends, people in society. But ultimately, 50 percent is their own environment. Living, existing is, to me, one of life’s requirements.

All it takes is someone just willing to be the one just listening. It can be a mental breakdown happening unwittingly, ultimately at any given time, even if one’s in their prime...there’s a variety of factors including not at all limited to one’s “genes,” all that they’re inherited throughout their own lineage.

It’s unpredictable like Mother Nature’s unknown almost deadly silent “Revenge.” an unforeseen lifelong battle, a war that rages from within one’s “psyche.” They’re intelligent, their mind their own brain, turning against themselves. Thinking and seeing even your own flesh and blood, friends, family, and innocent people as the ENEMY! It can in a sense, for instance, be overcome. But the damage may never be undone.

I believe EVEN when one’s mind may deceive themselves when one receives more than just support and also therapeutic tools and also therapy they’re somewhat accepted and also newly learned coping skills is part of some sort of humanity’s recovery process.

In all of our own communities, spreading and teaching all others that the Normal stereotypical stigmata with “Mental Illness” assumptions that they, the sick person, must be crazy or have “schizophrenia,” not just influences one’s mania and or paranoid delusions, but is and can be detrimental to the person as in their whole well-being.

Seeing that [through] their own eyes, being empathetic and being sympathetic, is more than therapeutic, more than just understanding. It’s, well, that moment, mentally, that can change one’s life, and impact influence on one’s path, their life, for the better.

Soon, I hope and pray, one day also I wish it won’t be so strange. But become the “Normal.” Accepting, not letting one become a casualty of a relentless, ruthless war Mental Illness, Disorders, Disabilities, I believe are, Misunderstood.

Losing sight of our individual abilities creates our own instabilities. But in our societies without education, there’s more than just a hesitation dealing with such diagnoses leading to society’s prognoses that they're unwanted, incapable of being equal.

It's like a child’s inescapable worst night terror, society’s own, endless nightmare to compare their normal with another deprives our own understanding and comprehension and only describes humanity as a whole as born naive, moronic, retarded “stunting our growth.”

Our only reprieve is that we can no longer pretend like everything is acceptable, keeping another person down. With learning and experience comes wisdom. When an individual person loses their humility, they’ve all but lost their own humanity, and also their own morals.

Acceptance and understanding irrevocably are not just influential but consequential, not at all coincidental, in enhancing, not changing, improving one’s development. Advancing them and others. Not just glancing back, enhancing one’s life for the better.

Along with many and all cultures, a great many peoples and all walks of life, tribes and also individuals in all societies: Changing society’s preconceived nations will invoke emotions but revoke even Nations of Peoples taught generally untrue prejudgments of Mental Health.

One day, we can all say we’ve fought and not forgotten how rotten people used to treat each other. It’ll become, I do believe, more than just a dream, and also a movement.

Poetry - "Break In Silence"

Break In Silence

by M.C. MoHagani Magnetek

About life on the equinox

Like I know the what is and what nots

Slung over bones and grave insights

That cosmically spiral on late nights

Into places between spaces

I am looking for traces

Of strength. I need help. I have lost my way

Don’t think I’m going to make it another day

There are no beginnings and it never ends

Alone isolated loneliness no friends

For all of my nerves are bad

I can’t help but feel sad

I can’t help but be funky

A no bath having food and television junky

Laying around depressed on myself

I’m not the same as everyone else

Its just can’t be me in bubbles

With rainbows in troubles

From rising too high too fast

burst smash pop crash

My soul on ice, heart on fire

I sure do miss true desire

To feel better

So please come hangout with me later

Cuz right now, I am a hot mess

Constant turmoil. I digress.

by M.C. MoHagani Magnetek

About life on the equinox

Like I know the what is and what nots

Slung over bones and grave insights

That cosmically spiral on late nights

Into places between spaces

I am looking for traces

Of strength. I need help. I have lost my way

Don’t think I’m going to make it another day

There are no beginnings and it never ends

Alone isolated loneliness no friends

For all of my nerves are bad

I can’t help but feel sad

I can’t help but be funky

A no bath having food and television junky

Laying around depressed on myself

I’m not the same as everyone else

Its just can’t be me in bubbles

With rainbows in troubles

From rising too high too fast

burst smash pop crash

My soul on ice, heart on fire

I sure do miss true desire

To feel better

So please come hangout with me later

Cuz right now, I am a hot mess

Constant turmoil. I digress.

Art - "Self-Sabotage"

Self-Sabotage, Donalen Rojas Bowers, 2022

This piece focuses on breaking the silence around self-harm. Listen to Donalen's full story in the podcast episode "Breaking the silence around self-harm." You can see more of Donalen's work at @donalenbowers.

Advice from a therapist

Advice from a Therapist

Parinita Shetty is a therapist with VOA Alaska, which provides mental health services for youth in Alaska. During this episode she provided tips for breaking the silence around mental health. She recommends checking out Seize the Awkward, too, for some specific conversation starters.

Conversation highlights

- Looking after your mental health is not selfish. It's part of looking out for people you love.

- It takes courage to open up about mental health. Talking about it shows your strength.

- You don't have to start conversations with heavy topics. Just checking in on friends and others is a great way to get people to open up. Just be present.

- Don't use "you" statements. Use "I" statements. "I am concerned about..." "I have noticed..."

- Check your own biases. Don't assume you understand someone. Don't assume you understand their cultural background.

- Don't give advice. Listening is often enough.

Parinita's favorite Instagram mental health accounts

- therapyforwomen - Amanda E. White

- nedratawwab – Nedra Glover Tawwab

- estherperelofficial – Esther Perel

- the.holistic.psychologist – Dr. Nicole LePera

- conscious.re.parenting - Inez

- queersextherapy - Casey Tanner

- holisticallygrace - Maria Sosa

Other Instagram accounts to consider are...

- therapyforblackgirls - Dr. Joy Harden Bradford

- melodyhopeli - Melody Hope Li

- thefatsextherapist - Sonalee Rashatwar (they/he) LCSW MEd

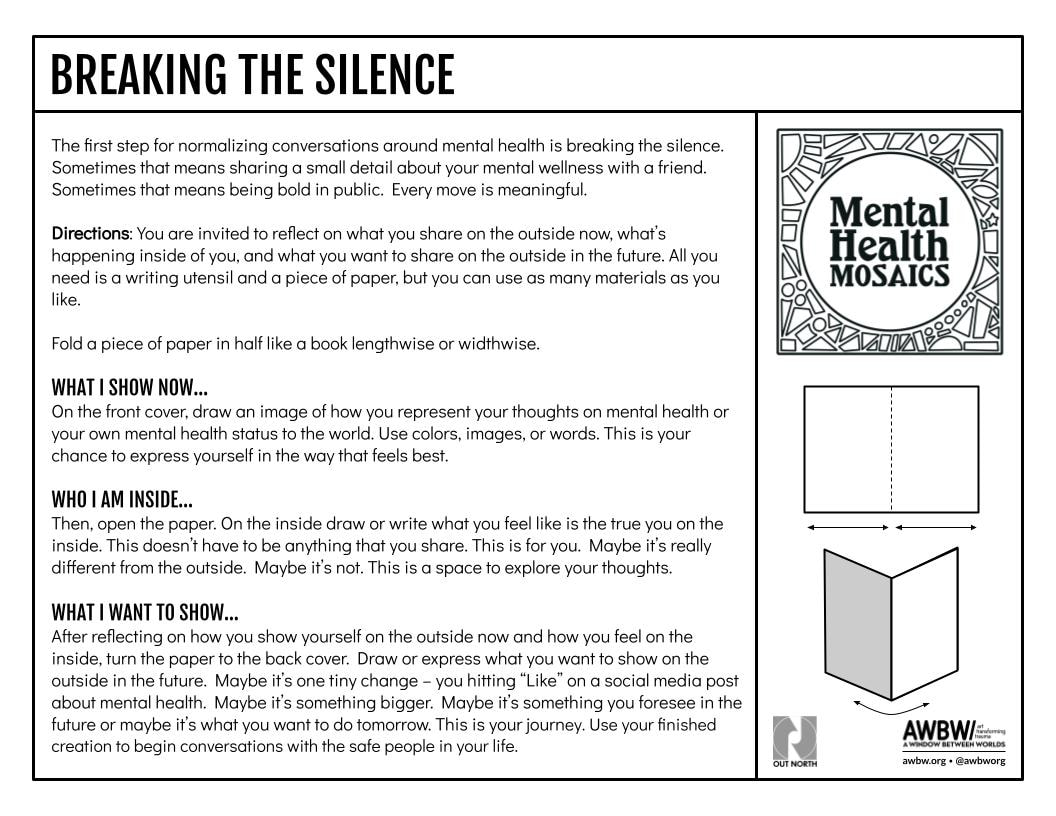

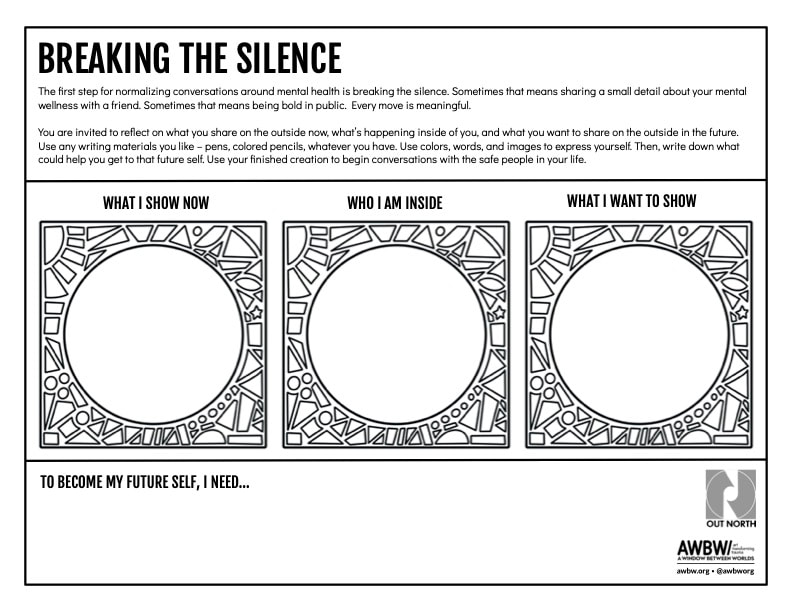

Worksheets

Worksheets

Mental Health Mosaics is collaborating with A Window Between Worlds to create activities that align with each of the podcast topics. This is a chance for you to process some of your thoughts and feelings associated with breaking the silence. You do not need a printer to do these activities, just a piece of paper and a writing utensil. You can print the worksheets if you want and use them for free in all situations. Find other worksheets here.

Thank you to Cathy Salser, Rudy Hernandez, and Martine Philippe from A Window Between Worlds for making these worksheets possible!

Thank you to Cathy Salser, Rudy Hernandez, and Martine Philippe from A Window Between Worlds for making these worksheets possible!

Transcripts

Full Episode Transcripts

Breaking the Silence

Self-harm

Breaking the Silence

[00:00:00] Anne: Welcome to Mental Health Mosaics, an exploration of mental health from Out North, which is located on the unceded traditional lands of the Dena'ina People in Anchorage, Alaska. I'm Anne Hillman.

If you've decided to listen to a show called "Mental Health Mosaics" then you probably already know that mental health is an important topic -- it always has been and the pandemic has made it even more so. Maybe you know someone who is out and proud about their mental health issues -- bad and good. Maybe you know someone who isn't. Maybe that someone is you.

The idea behind Mental Health Mosaics is to dig deeper into the issues surrounding mental health using this podcast as well as art exhibits and online resources. We at Out North are trying to move beyond the important but short comments you often see on social media, like ‘it's okay to not be okay’and ‘we need to take self-care seriously.’ Those are so true but they just touch the surface. And as a warning, some if not all, of these episodes contain triggers. We're talking about addiction, suicide, depression, trauma, and pain. We're also talking about recovery, healing, coping, thriving, and joy. We're centering the voices of people with lived experiences like Ralph Sara:

[00:01:24] Ralph: I thought to myself, "How can we help other people if we're not out there and proud of being in recovery?" You know, why can't we, you know, tell people our stories so they don't feel like they're alone out there?

And Jered Mayer:

[00:01:41] Jered: While there's that sense of validation that someone recognizes a specific problem, it was difficult for me to not initially just still feel broken.

[00:01:54] Anne: And Amy Urbach:

[00:01:55] Amy: I was really controlling, I was really insecure. I mean, a lot of the things that I did just seemed --they really seemed crazy to me, but at the same time it was like, this is how I am. It's so weird to look back on it now because I don't feel that way anymore.

[00:02:20] Anne: All of these folks will be included in future episodes, so subscribe to the podcast and you'll hear much more from them.

Like so many other people -- one in five adults in the U.S. in fact -- I've dealt with my own share of mental health issues. I've gone through the fun process of trying to find an antidepressant that didn't cause more harm than good. I've been paralyzed by anxiety and fear when trying to hike up a trail or to drive down the highway. But my experiences are limited and buffeted by my privilegepriveledge -- I'm economically stable, I'm white, I have insurance, I have a supportive wife who helps me work through whatever is going on. Heck, I even like my entire family.

That's why this show isn't just filled with what I think is important. I'm following the guidance of an advisory board of people with a huge variety of lived experiences. Some have experienced houselessness, others have been institutionalized. Some are healers, some are in recovery. All hold deep wisdom well beyond what I bring to the table. Through lengthy and personal conversations, the advisory board chose 10ten topics for the first series of Mosaics podcasts.

I'm also getting guidance through a partnership with NAMI - Anchorage, the local chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness. This is a group project, I'm just the voice leading you through it. You can read more about the advisory board and access other resources including art and creative activities on our website mental health mosaics. dot org.

To start the series, I want to introduce you to Martha Binkley, who speaks very openly about what it's like to have a serious mental illness. She was born and raised in Alaska -- her family is from the Bethel area and she spent some of her childhood in Kwethluk. She identifies mostly as Yup'ik Eskimo -- her words -- as well as African-American and Caucasian.

In 2007, when she was in her late 20s, she was diagnosed as having PTSD though she says some doctors diagnosed her with bipolar disorder and others with schizophrenia. Labels are not always clear. But she says she knows she's seen the world differently since she was a child.

[00:04:48] Martha: I've always known I have PTSD since I was two- and- a- half years old. It's been documented twice and actually, it's been documented multiple times over the years since '07. But I didn't know when I was younger, how to treat my PTSD or how to embrace it and accept it and actually, you know, embrace it and learn from it.

[00:05:12] Anne: She says she grew up feeling like an outcast.

Martha spent hours teaching me about her life as we sat in the various hotel rooms she at that point called home. When we spoke an agency was helping her she seek long-term housing. She shared detailed, vivid memories from her infancy and what it's like to have hallucinations of horrible events. Though she used to be a personal care assistant for elders, she's currently on full-time disability because of her mental health conditions and has a conservator, which means she doesn't have control over her own finances. She says that sometimes that changes the way people treat her -- but not always.

[00:05:57] Martha: Like when I go into GCI, they're like, "Oh, she has a conservator." Cause it comes up red flaggedflaged on my paperwork. So when they talk to me, they're not actually speaking to me directly. This last time I went into GCI, that young man, he spoke to me directly. He didn't look over at my daughter and go, "Um, which plan was that she wanted?" And my daughter didn't have to look at me and say, "Mom, which plan was that you wanted?"

With people who I deal with now, they don't necessarily all treat me like I'm a baby anymore. Like I need to be coddled or be explained down to as much.

[00:06:40] Anne: She says she feels like she encounters the most challenges with the way medical providers treat her -- arguably the people who need to listen the most.

[00:06:51] Martha: In the medical field, I mean, most people just, "Oh, you poor thing. No, we'll get you some medicine, and medicine will help you all work out. You know, just breathe. It's okay." But it's their tone. "Oh, you poor little baby" is what I hear, what it sounds like.

[00:07:10] Anne: So it's not like calming. It's --

[00:07:11] Martha: condescending. Exactly. And I tell people, I said, "If you didn't know that I had a mental health disorder, disease or issues."

I said, "I know my files are red flagged to only tell me certain things about my own health." I said, "That to me is illegal." I said, "For me to have to wonder what you're telling my ex or if you call my daughter or my ex, instead of addressing me," I said, "that's more than just rude."

[00:07:45] Anne: They're removing your agency and your power.

[00:07:48] Martha: Exactly, exactly. How am I to be attentive to my mental health if you don't tell me something? How am I supposed to know? I'm not clairvoyant. I can't read your mind. It's me, the one taking the medicine. No one else is taking it for me. I have to remind myself every single day. And it's so routine now that I'm not actually reminding myself every single day, but it's become a habit that I take my meds.

[00:08:16] Anne: Martha says taking her meds helps her to experience the world in the same way as most people. Without them, she sees things like tracers.

[00:08:26] Martha: I mean most people are just like, "What do you mean seeing tracers?"

I said, "Like, if you were to run really fast and have 10ten of you running after you that looked like a cut out of the dolls running. That's what I see with tracers. I mean, I did that as an example, when I was younger to a doctor, I said, "This is what it looks like, tracers is like this."

[00:08:48] Anne: So it'd be like there's a whole bunch of me's.

[00:08:50] Martha: Yeah, exactly, exactly.

[00:08:52] Anne: That makes a lot of sense. And is it just with people?

[00:08:54] Martha: Mainly with people. Like, or if they're holding something that goes really fast. Sometimes I make the inference and refer back to like if you did a big bubble and turn around and there goes all the tracer bubbles after them.

Oh yeah. Like if there were 10 versions of you chasing you, lingering right behind you. I don't think it's technically hallucinating. I mean, I'm not seeing somebody that's not really there. It's just that I'm seeing multiples of them that I know, you know, it could just be the way my brain processes things and distributes the information to my opticals, my optical nerves. When I'm looking at something and then realize, "Oh, it's like a movie playing." And I'm like, "Oh man, I got to shut the movie off in my head!" Cause sometimes it will come on automatically.

[00:09:54] Anne: Martha experiences life very differently than most people and she knows it. She also knows that doesn't mean that she's less than anyone else or that she's stupid or that she should be pitied.

[00:10:08] Martha: Just because I have mental health issues doesn't define me as a person that way. I don't let it define me as a person that is seen with having mental health disorders or issues. Or that it's a disadvantage to me. I look at it as rather an advantage that I have. That I can empathize with somebody else who actually is similar. And you never know anybody, especially after this pandemic, there can be many with PTSD issues that have never been homeless before and never had to face such atrocities as whether or not you're digging in the Ddumpster for food or not. Having a place to live and sleep. For most people have never experienced that for once they experience not, usually they end up getting diagnosed with PTSD of some sort. (Ringing phone)

Anne: Our conversation went on even after the phone call. For Martha, talking about mental health isn't a challenge. It's part of her daily life that can't be ignored or sidestepped. I mean, even her phone provider knows she has a diagnosis. You can read an essay Martha wrote about living with a mental health condition and see some of her self-portraits by going to mentalhealthmoasaics.org health mosaics dot org.

[00:11:34] Anne: Sometimes the best way to help people start breaking the silence around mental health is through art and poetry. M.C. MoHagani Magnetek is an Anchorage poet, writer, and performer. She's also Mental Health Mosaics' poet-in-residence. She adapted a poem she originally wrote in 2015 for this episode.

[00:11:53] MoHagani: About life on the Equinox.

Like I know the what is and what nots

Slung over bones and grave insights

That cosmically spiral on late nights

into places between spaces

I am looking for traces

of strength. I need help. I have lost my way

don't think I'm going to make it another day.

There are no beginnings and it never ends.

Alone isolated loneliness no friends

For all of my nerves are bad

I can't help but feel sad.

I can't help but be funky

a no bath having food and television junky

laying around depressed on myself

I'm not the same as everyone else.

ItIts just can't be me in bubbles

With rainbows and troubles

From rising too high too fast

burst smash pop crash

my soul on ice, heart on fire

I sure do miss true desire

to feel better

so please come hang out with me later

Cuz right now I am a hot mess.

Constant turmoil. I digress

Break in silence.

But to explain it, you know, life on the Equinox, so being bipolar is like, you know, there's this constant balance between ups and downs, highs and lows, mania and depression.

So this Equinox, you know, in, in a sense, in terms of seasons, seasons and metaphors. And it's like, you know, I know what is and what isn't. However, you know, this is like it's in my bones. It's it's grave. It's chronic illness, is what it is. And it doesn't, it doesn't go anywhere. And it's like this constantly spiraling up into mania, spiraling down in depression. And in here I said, so "I'm looking for traces in between spaces" because, like, things are constantly moving in and out -- my emotions, my wellbeing.

Like how, the ideas that, like the suicidal ideations. I, it's like, I'm just searching for a strength in anywhere that I can find it in this, like, whirlwind of emotions. And I'm constantly going to. And like I said, it's chronic, it has no beginning and it has no end. So, it's just, it's there.

And even though I have a support group --, I have family, I have friends -- . I'm still alone in my thoughts and my feelings and what I'm going through. I think of many people who talk about mental wellness, mental illness will say the same. No matter how much, like, support is there and the people that surround us is there, it still feels like alone in the struggle.

[00:15:09] Anne: This is Anne cutting in real quick. MoHagani actually gave me a line-by-line explanation of her poem, but I wanted to give listeners a chance to think about it on their own instead of including it all here. You can find MoHagani's complete explanation on the Mental Health Mosaics website or read the text of the poem there to yourself. And yes -- I'm just trying to entice you to go there to check out all of our resources. Ok, back to the interview.

Why is this poem breaking the silence for you? What made you associate this all together with breaking the silence?

[00:15:50] MoHagani: Like, so when I wrote this poem originally, I was lashing out and I was crying out. I would say, like to the universe. And in the first version of this poem, I was speaking to John Coltrane, Billie Holiday, and Gil Scott-Heron. You know, jazz musicians and poets and stuff.

So I was just like, just crying out to universe, crying out to the ancestors. I'm not going to be silent. I'm going to say something. So, to break the silence and break it like abruptly and like definitively is what this poem does. Because it's very difficult for people.

The first time I was involved in group therapy, I think it was 2011. And it was like 20, maybe 30 people in this day room all day and in group therapy. And out of all of those people, none of them could talk about their mental health outside that room because of their jobs, because of their families, you know, the stigma and all of those types of things.

And I don't, necessarily wasn't, in a position to do that either, but I was like, you know what, no matter what I do, from here on out, I'm going to be vocal about my mental health and wellbeing for people who can't do it. And I mean, it's a good thing that I am because, like, there are oftentimes when I talk about mental health publicly, I'm making maybe like posts on social media about it. And just say it's just like 10ten "Likes" and comments on this thing, and like, "Oh, cool, right?" But then there's like another, like, 15 people who don't "like" or comment on it, but they'll like privately inbox me. Or when I see them out in public or something, they just like call me on the phone and say, "Yo, MoHagani like, thanks for sharing that experience." I mean, the stigma is so real they don't even want to hit the little "Like" button. You know, ‘cause they don't want nobody to know that they liked this idea, this conversation of mental health, that they identify with it in some way, shape or form. It's that deep. Right.

And so knowing that I know that it's important that I talk about it openly for people who are not able to talk about it. And then I have some other friends out there. I have another friend-- I don't know where she's at, I think she's in North Carolina and now--she's somewhere on the east coast.

She's a beautiful singer. And she openly talks about her struggles with sobriety and alcoholism, her struggles with depression and everything. And it's just wonderful to know, like, there are other mental health wellness warriors out there. There's other prayer warriors out there.

Like, "Yeah, go ahead and do it!" Or whatever.

You helped more people than you know. You never know who is listening. And when we talk about mental illnesses and stuff, we're talking about invisible things that you don't see on the surface. Just because a person is all smiles and they glitter and go, don't mean they're like, they're not tar or dirt and yuck all underneath all of that and everything.

So it's just important. So like with this poem, it's breaking the silence on that, not just for myself but for others, too. And then the space can be made safe. But it only happens when we speak up and speak out, you know? Otherwise, you're just like suffer like silently alone and in your own thoughts and feelings. And it gets really rough.

And a lot of times, you know, many suicides and suicide attempts, it comes from isolation. If there's different components to what gets a person to that point of wanting to cause self-harm to oneself. The one thing, that final thing, is isolation.

Right? And then also knowing that, like I knew a young person that, that left here a few years ago, but they madey sure that they was totally isolated. Even though they told -- they kind of sent these signals out at the last minute that they was going to do this, but they also made sure they was in a space where no one could get to them.

And so they could just, you know, pass on as the way they did. So, but they felt isolated long before that, you know? And so we don't want people to feel isolated under no circumstances.

[00:20:51] Anne: As MoHagani says, we don't want anyone to feel isolated which means we need to be able to talk about mental health. To get some advice on how to do that, I spoke with Parinita Shetty. She's a counselor with VOA Alaska, an organization that provides therapy and support for children and teenagers. She grew up in India and now she's based at a high school in Anchorage. We spoke about how to start conversations around mental health, something she has seen people struggle with her whole life. A lot of this conversation is about talking to youth, but the pointers are applicable to everyone.

[00:21:33] Parinita: I guess growing up it was never part of, at least in my culture, it's not part of something we talk about. Mental health is not commonly spoken about. It's becoming more of a conversation that is more mainstream right now with more celebrities talking about it, and the younger generations being more open to it, especially on social media.

That's absolutely awesome. And it's exciting because it's still --so there's so much stigma around talking about mental health and talking about your own needs or wanting to fulfill your own mental health needs. So coming from a collectivistic culture, that kind of feels like you're being selfish or you're going against the culture because you're standing up for yourself for talking about your own needs.

But that's not the case. It's not selfish to ask for help. It's not selfish to want to better your mental health.

[00:22:26] Anne: So when you say mental health, like, that means so many different things to so many different people. What do you mean when you say it or when you hear it?

[00:22:35] Parinita: So the way I look at it is, the brain is a part of your body and like how we take care of our physical health. We need to do things to maintain our physical health. And then there are days that we're not doing so well and we need to put in more effort to take care of our health. I look at mental health similarly, in terms of it's something that's an ongoing thing that you have to work towards.

Even if you're having a great week and this week has been fabulous, it's still important to make some space for yourself to take care of yourself, do some self-careself care. And if you're having a tough time then putting in some more effort by talking to people, seeking professional help. That's really key.

[00:23:19] Anne: So why is looking after yourself not selfish?

[00:23:25] Parinita: Let's say because all of us deserve to be happy. All of us deserve to find the connection with others, to find love. We deserve to be loved. We are worthy. It gets difficult to think that way when you're struggling with anxiety or depression. Your brain is trying to trick you into thinking that you are alone or this is endless and there's no one out there who's going to understand me.

And having these conversations helps you feel like there is someone who can understand me, there is someone I can connect to. So it's really important for me, at least, to reach out to people around me and also support people who reach out to me. So that's why I don't feel like it's selfish or in any way self-serving. We put an effort to take care of people we love and loving ourselves also includes taking care of ourselves.

[00:24:24] Anne: Oh, I've never heard it framed that way before, but I really appreciate that a lot. I really appreciate that a lot.

So if someone comes from a family where bringing up mental health doesn't happen, like someone in their family says it's a weakness or the culture around them says it's a weakness. I often hear that especially with men. How do you move past that and bring it up anyhow?

[00:24:57] Parinita: I feel like a lot of people think that not talking about it is gonna help it go away or they can push it away by not talking about it. But it's the opposite. The more you talk about it, the more it lessens that stigma. And it lessens the intensity of what you're feeling, that shame or guilt you're feeling for reaching out to someone. And there's a big stereotype that if you're seeking mental health, it means that you're weak or you're crazy, or something-- words like that are used. And it's so unhelpful.

And it's just getting that message out, that it's not weak to look after your mental health. It takes a lot of courage to open up to someone. Opening up to someone, involves being vulnerable, talking about your feelings. And that is really hard and it takes a lot of courage. So it's the exact opposite of being weak, if you ask me.

But yeah. And having someone, a trusted adult, a school counselor, a coach, a teacher a family member orof friend, anyone around you that you can just start having those conversations with. And then if you feel like you need more help or more intensive help you can go to someone who is a professional.

At our work, at least at VOA, we have peer support, we have case managers. So if it's not just the counselor that they're having one-on-one services with. There is a peer support specialist involved who helps with educational stuff, driver's license, getting employment, so life skills. And then we have family support programs to help the families who feel like they don't know what to do to help the client. Helping the families feel more supported so that they can support the client as well.

[00:26:46] Anne: Because I guess it goes back to even what you touched on earlier that we are, we as humans, our community, we as humans are collective. And so supporting not just the individual who may be struggling, but everybody around them as well is also really important.

[00:26:59] Parinita: Yeah. There's a lot of focus on self-careself care these days on social media, which I absolutely love. But also as humans, we strive to be heard and seen. We need that connection with others to survive. So it's self-careself care and that connection with yourself, but also working on that connection with others that's really important.

[00:27:22] Anne: That makes sense. And it almost seems like from what you're saying -- Well, a couple things that really jumped out at me. One, if we're taking care of ourselves and taking care of our mental health, it doesn't just mean talking to a therapist. It also means getting what you need to survive. So a driver's license, a job and feeling like you're part of something bigger.

And it also sounds like if we start reframing this as "I am courageous by talking about it." that's even a way you could start the conversation. Does that work? Have youth or adults, can they say, "Hey, listen, it's taking a lot of my strength to tell you this but..."

[00:28:00] Parinita: I have had a few students who have had to speak to their parents about it, or, they had to convince them that they needed mental health services, and they were advocating for themselves. And that was wonderful. Sometimes they don't have the words to say that, but helping them find those words and to speak their own truth, basically.

So yes, I have been inspired by some of my students who have been able to get their parents on board. That has been really nice to see.

[00:28:35] Anne: What advice would you give other youth or adults if they need to get somebody else onboard?

[00:28:40] Parinita: I would say just, you don't have to start off immediately by heavy topics or mental health. You can start off with a conversation. Check in and see how they're doing, and then maybe mention how you're doing.

And especially with kids who have to convince their parents it's helpful for parents to understand where they're coming from. Sometimes this resistance is more about how they perceive mental health and what their own biases are rather than what is happening with the child. So for a child to be able to just have those conversations, starting off with smaller conversations, and then explaining what they're going through, can sometimes help get parents on board.

[00:29:28] Anne: Is it sometimes the other way around that parents have to be convinced by their kids, "Hey, it'd be great if you could talk to someone or open up to someone?"

[00:29:36] Parinita: Yes, absolutely. And especially when they're younger and it's more difficult for them to feel like they have any kind of control. And then they have an adult or their parents telling them you have to go to therapy. That can be a little bit of a power dynamic issue where the child feels that they're just being controlled by a parent. And the parent feels like the child's not listening to me because they're disrespecting me or I don't have control over them. So just having conversations more in terms of there's nothing wrong with you. So when we use "you" statements like, "You are rebellious,." oOr, "You are acting up, ." iIt makes people feel defensive.

So starting with "I am concerned about you're not sleeping well," or you're not, "you've not been eating." So "I am concerned that you might not be getting the support you need from me. And yeah. Would you like talking to someone else who can help you with this?"

[00:30:42] Anne: I like that, "I'm concerned. I may not be giving you the support that you need." So it's yeah, so clearly, coming from a place of caring.

[00:30:52] Parinita: Okay. Because that is what it is. Parents are worried about their children. And they do want them to get support. With family,family it's very easy to step on each other's toes, exactly how to push each other's buttons, and we get stuck in those cycles. That cycles of communication that we're used to. So stepping aside from that and saying that I'm saying this from a place of concern, and this is coming from a place of love and caring, and I want to be able to support you.

[00:31:24] Anne: And it seems like something that like even a peer can say to a peer.

[00:31:28] Parinita: Yeah, absolutely. That's something you can tell a friend also, because you can be there for your friend, but at some point if you feel like this is over your head, or you're not qualified to deal with this, you don't have to be your friend's therapist. You just, you can support them without having to talk about heavy stuff. You can, like I said earlier, starting with smaller, check-ins smaller conversations, being there for a friend, regular check-ins, going out for a movie, going out to get something to eat.

And if you feel like there is something you are not equipped to deal with then suggesting that, "It sounds like this has been really hard for you. Do you feel like talking to a professional might help you?"

[00:32:14] Anne: But really starting with connections because even just those connections really are supportive.

So what happens if you're, like you had mentioned earlier, how coming from India, people don't talk about mental health. If you're from a culture or working or talking with someone from a culture where those conversations aren't open things, how do you do it? And I realized this is going to be different for every culture, but how do you do it in respectful ways where you're honoring where someone is from, who someone is with their identity, but also taking this step towards being open?

[00:32:51] Parinita: And that's a great question. First thing I would check, "what is my own cultural competency? What is what are my cultural values? And what have I grown up with that have led me to assume things about different cultures? So what are my assumptions that I'm bringing to the conversation before I even have that conversation with the person in front of me?"

And being aware of that is the first step to say that, this might be a blind spot for me, or this might be an area of growth for me where I can learn more or I need to learn more. And where can I find more information on this? And also just before assuming something it's better to ask. And it's always helpful to ask.

And I recently read something on social media. It was, "Curiosity breeds compassion, and judgment breeds resentment." And I really loved that. And I feel like it's really applicable to cultural conversations and multicultural conversations. So, at least in for us as therapists, also being more aware of, people's method of healing. Different people have different ways of coping. We might have someone who says that they find it more helpful to be involved with the spiritual or religious leaders. So including that as part of treatment and not focusing just on conventional Western cultural ways of dealing with mental health.

So being open to other perceptions or other beliefs on healing.

[00:34:34] Anne: I'd love to hear more about that healing, like different methods of healing.

[00:34:40] Parinita: So, I would say at least in some cultures, and in my culture also, there's a lot of focus on our soul and our body related to mental health. It's not just a biomedical issue. It's a community issue. That connection with others and healing our body and finding ways to listen to our body. And there's a lot of research on this as well on how our body gives us signs when something's not wrong with our mental health, our body is giving signals.

So listening to those signals and finding ways to, I guess, manage or cope with things by being more in tune with your body.

[00:35:21] Anne: Yeah. That's a tough one. At least speaking from personal experience. That is a very tough one for me.

Okay. That all makes sense. I really appreciate the ‘make sure that you check your own assumptions, check your own biases’ when you're approaching these conversations.

I know that there's no step-by-step guide. I wish there was a user manual for these conversations. But how would you start it? Especially if you see someone struggling.

[00:35:51] Parinita: So if it's a friend, I would say being there for the friend consistently, and sometimes your friend might not want to share something that's personal or deep, and just understanding that maybe you're not the only person that they're talking to. It's not about you at that moment, and the way they react is not personal.

So just being there for them consistently and regularly checking in on them, making sure that you're doing things, if you have a hobby that both of you enjoy, doing activities together and that's a great way to just see how they're doing. And if you are concerned, make sure you're opening that avenue for having that conversation when they are ready to have it.

And a lot of times we do have similar experiences with others that makes, that helps us relate to their issues. So if they are hesitant about talking about their own issues, maybe starting the conversation by saying that this is something that I experienced and this is how I dealt with it or this was something that I was struggling with.

And while having that conversation, making sure that you're not really saying that, "if I were in your place, this is what I would do." Avoiding advice- giving and just being there to support them. Sharing your story to help them share their story rather than as a way to give advice or fix their problem for them.

[00:37:23] Anne: That is a fine line, isn't it? An easily crossed fine line.

[00:37:28] Parinita: It is. Because even if we have similar experiences, it's still not the same.

[00:37:34] Anne: Parinita spoke a lot about breaking the silence around mental health with people you know. But what about with strangers? What happens when you encounter someone who is clearly experiencing some sort of mental health issues in public? How do you help them? Should you? To talk about this I went to a place where everyone is welcome no matter what their situation in life – the Anchorage Public Library.

To be fully transparent, I am a big fan of the public library system. I go there all of the time, I donate to the library. In fact, I started writing these very words when sitting on the Loussac library lawn but I was interrupted by a stranger who just really wanted to talk. For a really long time about a lot of random stuff. Like I said, everyone goes to the library.

Ziona Brownlow is a community resource coordinator for the Anchorage Public Library. Her role is to help connect people with resources, like food or housing. Just like anyone can look for books or use the computers, anyone can walk in and speak with her and her colleague Rebecca Barker.

[00:38:51] Ziona: And there's just these certain barriers that other settings might come with that the library just doesn't really have. I think we have our own unique barriers, but it's such a neutral setting that I feel like it allows people to show up as their whole selves. They're not presenting in a certain way so it's documented how they would like it to be, or they're not presenting in a certain way so that you do give them access to this resource. Like they know that if they come to the library, I have a question and it's probably going to get answered.

[00:39:17] Anne: One of the people answering those questions is Alaska collection librarian Sarah Preskitt. She spends much of the day interacting with patrons and answering questions ranging from where do I get info on 17th-century17th century French nuns to how do I seek housing. She regularly meets people from all walks of life who are having mental health crisescrisises.

[00:39:40] Sarah: So it really depends on each patron. So if you have a patron that's having a mental health crisis, you check in with them, "Hey, are you doing okay?"

That's of course after you've checked in with yourself, am I okay with this? Am I okay to help this patron move forward? Are they okay? "Is there anything I can do to help you today?" Calmly as you can. If someone's yelling, that's really hard. If someone is at, you know what Rebecca called a 10, sometimes an 11, coming in with, "Hey, are you doing all right?" in your calm SNL-NPR voice --that's what I think of it as. "How are you doing today?" Sometimes they'll tell you right away, "I've got this, I've got this, I've got this. And I just can't." A lot of times it's "Get out of my face."

All right, I will get out of your face. Then you have to analyze that situation of "Is this interfering with anybody else's use of the library?" And that's the key part. If it's a situation where again, someone's just pacing back and forth, they're not interfering with anybody's use of the library.

If they're yelling at other patrons, that's interfering with their use of the library. So being able to understand that difference and how you move forward with that. If they're yelling at other patrons then you really can just tell them, "I'm sorry. You can't yell at other patrons in the library.

Let's come over here to this open space over here and see what we can do." Again from there, if they follow you, then at that point, I might call CRC team to see if they can help out.

[00:41:13] Anne: That's the community resource coordinators, like Ziona and Rebecca. They're trained social workers who can support everyone.

[00:41:20] Sarah: You want to do everything you can to deescalate a situation and sometimes successful. Sometimes it's not because that's just not where that person is that day.

You have to be nonjudgmentalnon-judgemental. You cannot tell the person that, "Well, you're wrong. There's nobody talking to you. " You know, “Don't do that.”

And sometimes we do call security. If it's become a situation where like CRC is not available, you've used all the tools in your toolbox to try to get to the heart of what this person is experiencing, and it's just not a good day for them to be in the library. So we'll discuss options, usually it's just let's try again tomorrow.

And they'll come back and they'll be fine, it'll be fine. And sometimes you can get them to talk about what it is they need and you can get them to that resource, whatever that looks like. I did sit with one woman for, I think two hours just having a panic attack. She saw someone in the library that was in the community, someone from her past, and it's night and day, you can't control panic attacks.

And it might have made other patrons uncomfortable, but she couldn't see them. When you're having a panic attack, it's fog. You don't really understand what's happening. So you sit with a person and say, "Yeah, I'm here. I will be here when you need me." And in her case we called emergency services because she needed that assistance and that was the right call in the moment.

[00:42:45] Anne: Sarah's story has a lot of pieces to it. One point that was emphasized over and over by all three women was that when you are working with a person who may need help, you need to look into yourself first. Ziona elaborates on this -- she says people in public-facing roles in the community need to understand why they react to people and their actions in certain ways. She says if someone says they can't work with or help a person, she wants to know why.

[00:43:20] Ziona: I think the first thing I would ask them is like, "Why is that making you uncomfortable?" Because that's important for me to know, right? Does the person remind you of your uncle that you have sexual trauma with? That's important for me to know. And maybe you won't disclose all of that, but that's different than -- it's important to differentiate -- is it this? Or is it, "I'm scared because this is a large person", or "I'm scared because they're speaking to you in such a loud voice."

That's something I personally struggle with. So this might be something like I have to ask myself, like, "Why do I not want to serve this customer? Okay. Because I have my own personal biases as humans do. And this person is checking those boxes for me."

So the next step is one, like I've already acknowledged what it is for me, is it something that I can move past? Yes or no.

[00:44:05] Anne: Rebecca says you have to assess your biases because that changes how you view what's happening around you when someone is acting differently.

[00:44:14] Rebecca: So much of that depends on who's telling the story and how, right? And who is the main character in the story.

You see it one way and it's, "Yes, this was dangerous. This was violent. This was et cetera." Versus if you see another way, it's like, "This was illness. This was disability. This was lack of empowerment to access resources. This was isolation and adapting."

And I think just being aware that, like, discomfort means a lot of different things. It's almost an unhelpful word other than it means more examination is needed. I think it's like discomfort might be the lived equivalent of when a researcher says "More studies needed." Because you got to get a little bit deeper in there.

Because there is discomfort that's based on actual harm or actual risk. And then there's discomfort that's based on displacing privilege or just pressure to think of something a different way. Those are both -- discomfort can be used both those ways. So we have to examine the codes that we're using when we talk about those things.

[00:45:08] Ziona: I think the reason why I emphasize checking in with yourself and exploring like that discomfort so much is because there is so much power in how we describe somebody's behavior and how we document something happening.

The words that we use to describe this experience could be either what makes or breaks APD [Anchorage Police Department] being called or what makes or breaks a charge actually being pressed. And because we are human, we are subject to being fallible, to not being objective or to overemphasizing something or to under emphasizing something.

And I think that's, I think that's the reason why I emphasize that so much is because, especially in a position of power when we are writing incident reports, when we are documenting in medical charts, when we are making police reports, it's really important how we communicate things. Because what somebody could be experiencing that is observed to be dangerous or offensive, that person who is experiencing this right, who you're observing, like they could be experiencing something that's so scary.

And it's resulting in them acting in a way that's peculiar. And now you're scared because this behavior is peculiar.

[00:46:23] Anne: So how do we make sure that what happens from there doesn't turn out badly for anyone? Rebecca puts forth a suggestion that everyone can use:

[00:46:34] Rebecca: You have to get curious about what's going on.

And I think one of the key questions that's usually repeated in trauma-informed care is how to frame that question from, "What's wrong with you?" to "What is happening with you? Or what happened with you?" That you're in this situation, whether it's maybe you're yelling, maybe you're throwing rocks, maybe you are pacing or agitated . ThatThat person's going through something.

And, does that mean that you need to run up and give them a hug? No, that's not appropriate. You don't have that relationship with them. So let's get curious about what's going on. Do we recognize that this is a safe environment? Is there anything that is unsafe about this? Or is this person just pacing back and forth and talking to themselves?

Can you maybe say, "Oh, hi, excuse me, can I help you with anything?" Can you just gently can if somebody is at a 10, can you bring a two- and- a- half and just say, " Oh, hey, what's going on?" Get curious and kind and give them a respectful amount of space. Nobody wants to feel hounded at any point. Personally, I don't even if I'm shopping or something like that, "Don't talk to me."

So let's have that empathy and shared experience and just go for just like anybody else "Hey, what's going on? Are you okay?" Just check in. And if you're, if they're fine, then they're fine. And let that difference just exist.

[00:47:45] Anne: Rebecca, Ziona, and Sarah all acknowledge that even if just treating people with dignity and respect is a straightforwardstraightfoward idea, that doesn't mean it's always easy to do. We each carry with us our own grief, stress, trauma, and joy -- and our own mental health issues. This isn't an us-vs-them thing -- we all have mental health. For Sarah, she has to weigh how her own anxiety affects the way she perceivespreceives situations.

[00:48:14] Sarah: So I have lived with anxiety forever. I'm pretty open about that.

And I've learned in, say, the last 10 years or so that I need to check in with myself. Is this a me problem or is this a bigger problem? Am I anxious right now because something's telling me I should be anxious or because there's a conflict curation in front of me and there are many people in danger. Like figuring out where it is on that spectrum.

So what really helped me is to do it in situations that were low stakes, you know. "How do I feel about everybody in the room today? Okay. Okay. Oh, I'm getting a weird vibe from this person over here. Okay."

And you do those little check marks in situations where you're safe and you don't have to make any split second decisions. And so that way, when you do come to a situation that's maybe a little bit higher stakes where you need to make a fast decision, it's just muscle memory in your brain.

And you can just go through that checklist in three seconds and do that quick check in with yourself. And that's something that I think anybody can do, just not out loud necessarily. You don't want to be walking through Costco. "How do I feel about that person at the end of the aisle?" Don't do that, but you know, in your brain, you know, or maybe journal some things about it, especially if you have an interesting situation out and about one day and really reflect on it. So that way when it comes time, it's, you're not even thinking about it when you check in with yourself.

[00:49:34] Anne: Sarah says we also need to grapple with some society-wide ideas about mental health that create barriers for sympathy and acceptance of ourselves and others.

[00:49:44] Sarah: I think we need to move past this myth of people who are experiencing houselessness or mental health issues, just aren't up to the task or that they're not trying hard enough or that they're not working hard enough. That is not true. It's just not.

[00:50:01] Anne: And to be clear, Sarah is not saying that everyone who is houseless has mental health issues -- that's definitely not true. Nor is everyone who has experienced a crisis in public or in private worried about housing. Ever cried uncontrollably in public and just desperately hoped no one would see? I sure have. It sucks. Also,Also I have an amazing support network. Ever had library security chastisechastize you for misbehaving? Yup -- me again. Apparently you shouldn't take off your shoes in public. It's against fire code. What I'm getting at here is that we all have times when we need support or when we just need to be left alone.

[00:50:45] Sarah: I think that we need to recognize that the toughness that is part of our identity needs to include knowing when to ask for help, that it's okay to ask for help, that it is okay to recognize and say out loud that you need help with something.

[00:51:02] Anne: After putting together most of this episode, I sat down with Martha to see what she thought of it and of the librarians suggestions. Her reaction to Sarah was immediate.

[00:51:14] Martha: But most of that isn't her training at her job. It's the type of person she is. That's very unique and very commendable and admirable.

[00:51:24] Anne: And then, as with most conversations with Martha, we jumped straight into the next tangentially related thing.

[00:51:31] Anne: If you need help with something, like breaking the silence around mental health, you can find more resources at our website, mentalhealthmosaics.org health mosaics dot o-r-g. If you want to start breaking your own silence right this minute, stop listening to this and call 800-273-8255. It'sItsa suicide prevention line that will connect you with local resources. Thank you for listening to Mental Health Mosaics, a project from Out North. You can help others find it by rating us on any podcast platform or by forwarding a link to absolutely everyone on your contacts list. I recommend you do both.

This episode was edited by Susy Buchanan. Dave Waldron is the audio engineer. Aria Phillips wrote our theme music. Our poet-in-residence is MC MoHagani Magnetek. And I'm your host and producer, Anne Hillman. Special thanks to Jason Lessard with NAMI-Anchorage and Erin Willihan with Out North for reviewing this episode. We received funding from the Alaska Mental Health Trust Authority, the Alaska Center for Excellence in Journalism, and the Alaska State Council on the Arts. Check out the website to find outour more about our financial supporters and upcoming events and to donate. You can even find worksheets and art to prompt deeper thoughts about this topic. Now please go start talking about mental health!

Self-harm

Breaking the Silence about Self-harm

[00:00:00] Anne: Welcome to Mental Health Mosaics from Out North, an arts non-profit located in Anchorage, Alaska on the unceded traditional lands of the Dena'ina People. I'm Anne Hillman.

A note before we get into my interview with artist Donalen Rojas Bowers. The episode discusses self-harm, internet predators, sexual abuse, and emotional abuse. If these issues may trigger you, consider listening in the company of a trusted friend or family member, or have a person in mind who you can call in case you need help while listening. Keep in mind, you can always reach out for help from the people at the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline -- they are there to listen and to connect you with resources, even if suicide has never crossed your mind. That number is 1-800-273-8255.

Now I want to introduce you to Donalen Rojas Bowers, one of Mental Health Mosaics' featured artists.

[00:01:49] Donalen: my name is Donalen Rojas Bowers. I'm a first-generation Filipino American.

Um, so my mom was born in the Philippines and my dad is from here and the U S and so I'm half Filipino and I'm really proud of that. I'm uh, I'm actually the first, Generation to go to college too, because my mom went to some college in the Philippines, but, um, it doesn't count here, I guess. So I'm technically considered the first generation to go to college, which is something that they're really proud of and I'm graduating in May.

[00:02:20] Anne: Donalen works in watercolors and embroidery. She says her artwork is a journey that helps her better understand her life. Donalen is a survivor of both cancer and abuse. For the Mosaics art show, she embroidered an image of her arm, the skin marked with scars from self-inflicted cuts. But the marks don't tell Donalen's whole story. Extending from the scars are beaded threads that transform into butterflies.

For Donalen, creating the piece was one way for her to break the silence about mental health issues, including self-harm stemming from sexual and emotional abuse. Sharing her story is another way. She said listening to other sexual abuse survior stories helped her heal, so she wants to do the same for others.

[00:03:08] Donalen: It's crazy how much perspective it gives you, um, understanding that you're not the only person that is, suffering in this, in that way.

And you're not the only person who doesn't like understand why things are happening the way they are and doesn't understand like why life has to be this way. Like it's, it's, it's something that's really hard sometimes. And I think that understanding that you're not the only one going through that is really helpful because.

You can feel like there's some solidarity between you and other people. And, and like in this shared human experience that has its ups and downs.

Anne: This Is Donalen's story.

Donalen: So I had a complicated, like, I dunno, teenage hood and my, my family had no had no part to do with this at all. They, they were loving and caring and they did everything they were supposed to do, but I was groomed on the internet, um, by. People to were definitely pedophiles now that I'm looking back at it.

Yeah, definitely pedophiles. Um, and they, they groomed me from the time I was like 13 to the time I graduated high school and it was not the same person, but, um, there was one person who was grooming me for awhile, who, um, who caused a lot of my mental issues from, from like my younger days.

[00:04:35] Anne: And so as when you say grooming you, what do you, what do you mean exactly?

[00:04:38] Donalen: So, um, something that a lot of pedophiles and predators will do is groom

children, it's basically this. Like how you do your, like how you might teach a dog.

Like you give them positive reinforcement for good things and negative reinforcement for bad things, but it's not actually good and bad things. It's like, whatever they want you to do. So like, they will punish you and not talk to you. So do psychological torture by like, just ghosting you for like a week, even though they were saying they were going to call you the next day and then there'll be like, well, you didn't, you didn't do this.

So I'm not, I didn't talk to you for a week and they'll emotionally manipulate you. And they'll tell you things like, you know, if you don't do this all, you know, do this to your family or you will, I will like, I will have sex with someone else. And like, I'm like a 14 year old hearing this and it was really traumatic.

And so I had, I still deal with PTSD from that.

Normally, it's not even that they're trying to get you to do a specific thing. Um, every time they'd try to groom you, it's like, they're trying to get you into this mindset where you feel isolated or you feel like you can't talk to anyone.

You feel like everyone hates you or you feel like everyone's against you. I was told for years by someone I thought I loved and trusted that the, what my family was doing was like, even though it was just like normal stuff, like giving me a hug, like he was telling me like, well, that's malicious.

It was like, I couldn't like live without him.

Like I got to the point where I felt like if I did anything without talking to him first, I would get into so much trouble. It was such a like horrible experience that it made it really difficult to go through high school. I think that I felt like, how could anyone understand me?

I'm in a relationship. That's the law doesn't approve of because all of the losses ages. Yeah. But that, cause that's what they want you to think too. Like that's what they tell you like, oh, age is just a number. And then, you know, when people tell you things enough, you start to believe it. And I don't know, like, it's just, it's just so bad.

And they just run around on the internet saying all these things to kids and these kids are not like able to. You know, understand, like, I just didn't understand. Like I thought he was like my best friend. Like I was like, man, this guy is so awesome. He talks to me all the time. He's so nice. Like, no, he's, he's nice because he's trying to get something from you.

[00:07:09] Anne: Donalen said that when she was online, predators found her easily.

[00:07:14] Donalen: On the internet, um, you just can, I mean, pedophiles will literally go out of their way to find kids on the internet. So like, I mean, if you just exist on the internet, they'll message you so. You know, that's, that's, it's pretty easy to talk to them. It's not good, you know, it's, it's really like, I mean, especially if you have accounts as a kid and then, you know, any person can message you and they can say there are any age, you know, you can get on a dating site and say, oh yeah, I'm under 18.

And then they've talked to you and then they, you get to like, know them and you think that they're a certain age. And then they're like, oh, actually I'm this age. And, but then you already kind of like, know them and you like them and they're their friend. And you're like, okay, well, it's probably fine.

Like, they're only couple of years older than what they said they were. So it's not that bad, especially considering my parents are 13 years apart, but they met when my mom was like, twenty-something so it's different. Um, it's quite, quite a bit different. Um, she was still young, but not, not that young. Um, and so yeah, they just, it just, they just constantly barrage you with messages.

Like it's, it was insane. Like how the amount of like old men messaging me was disgusting, honestly. Thinking about that now it's like, literally disgusting. Like, I don't know why they would think that was okay. Or like they just do that all day. Like, I don't understand, like it's how is this so prevalent, but no one, no one really realizes how like at risk, like kids on the internet are like, I think that people are just now realizing they're like, oh yeah, internet is kind of dangerous.

I'm like, yeah, like really fricking dangerous. Yeah. I was coerced into taking nude pictures of myself as a like teenager. And, and I didn't know about that stuff really because no one really talked to me about it.

[00:08:54] Anne: Donalen said that she was confused and overwhelmed. She didn't want to tell the police what was going on because she was being blackmailed with the nude photos and she was worried that she would get in legal trouble for taking them.

[00:09:11] Donalen: I was a young girl and, and they didn't care that they were ruining my life and that they were causing me this horrible, traumatic, like, experience.

And that I was cutting myself because I was so distressed and I felt so alone. They didn't care. And so I want to say that, like, there are people that care. I, that was probably the scariest part of my life when I thought. No one cared because everyone was telling me no one cared.

So it didn't really help. And so I thought that I couldn't go to the law. I thought I couldn't go to my parents. I thought I couldn't go to the therapist because that's basically like going to like my parents or the law. And then I thought, I couldn't, like, I thought I couldn't even talk to my friends because I didn't think they would understand because obviously they would think that dating someone that old is bad and I'm like, oh no, in my head, it's not.

I don't want to hear that. I don't want to talk to them about that. So I was alone in my head. I wasn't really alone, but to me I was alone.

[00:10:10] Anne: Donalen was emotionally manipulated and sexually exploited through all of high school.

[00:10:15] Donalen: And, um, his end goal was basically to get me to another state. As soon as I graduated high school, I left my family. Two days later, I graduated high school and left on a plane two days later because I was ready to go to him. Cause that's what I thought I was supposed to be doing.

And it was not great. I mean, obviously someone who's malicious from the beginning just because of my age is not going to be great when you meet them. And so I had like a horrible two months in Arizona and then I, I couldn't even talk to my parents.

He took away my phone. I was pretty much held captive, although I was lucky in the sense that I didn't get, um, like I didn't get beaten as much as some of the other people. I mostly got mental abuse.

And so a lot of my issues don't lie with like the fact that, um, I was physically hurt. It was, it was mostly through my mental health.

[00:11:17] Anne: Donalen says she stayed with the man, who was a sex trafficker, until he was eventually arrested and she could return to Alaska. The trauma of the entire experience still impacts her mental health.

[00:11:30] Donalen: The grooming is not just like getting you to do things it's, it's tearing you down.

It's about making you feel bad about yourself too. Right? So I, as a teenager, I did self harm. And so that's kind of like what my piece is about the embroidery. It's about, um, the self-harm I inflicted upon myself as a teenager, um, on my arms, I used to cut myself and it was something that I didn't really understand at the time.

Um, I don't know, like, I'm not really sure why I started doing that. Um, I can't remember the first time. I think that a lot of people, that self harm don't necessarily have, like, whenever I do it, I don't necessarily have my right mind. Like it's, it's kind of like dissociating from like, you know, what's really going on.

So sometimes it's hard to remember, um, that stuff, but I remember that I was doing it in high school. And it was mostly around the times that, um, that guy would pop into my life whenever he would stop talking to me and then start talking to me again and stopped talking to me and started talking to me, it, it kind of coincided with that.

And for me, like seeing those scars can be really painful sometimes just because it reminds me of a time in my life where I was so confused and felt so alone. I thought that my parents didn't love me. I thought my sisters hated me. I was, I was thinking that everything was bad in my life because of this one person telling me this stuff constantly just whispering in my ear, telling me.

You know, your family's bad, your family's bad. Your family's bad, like all the time, but in different ways. So the people that are good at it are like, they do it so well that you won't notice until it's like way late. Like, I didn't realize what was going on until after like it abruptly ended. Like if he wasn't taken to prison and just like gone from my life, it would have been very hard for me to like leave him ever.

I couldn't, I couldn't bring myself to say no. Or leave because that's something that they don't want you to ever do. So they, they groom you to not, they, whenever you say no, they give you these severe consequences because they want you to not say no. So I never thought I could leave and I didn't think I ever could.

And I think that him getting like abruptly taken was probably the best thing for me.

[00:13:58] Anne: When Donalen returned home, she didn't just go right back to her old life with her family. She had to figure out how she fit in and what she wanted to do with her life now that it was hers again. She turned to art to process her experiences and, later, started therapy.

[00:14:19] Donalen: I had a hard time bringing myself to go to therapy for a long time, especially since they've had to come the phone and ask for help. And every person you called was like, yeah, we're not taking patients right now. I'm like, oh, great. I guess I'm just gonna now go cry in the corner. Like, like it's just, it's so much like trouble to get therapy, um, unless you have like cancer.

[00:14:42] Anne: A few years after returning to Alaska, Donalen was diagnosed with cancer. Her treatment lasted 18 months and she is now in remission.

[00:14:51] Donalen: So like for me, I didn't get therapy until I actually got diagnosed with cancer and they were like, here's therapy. Like they shove it at you because they want you to not be like. You know, like emotionally dying while you're like physically dying, I guess.

[00:15:04] Anne: It was during this time that Donalen finally started processing all she had been through because of the online predator who abused her.

[00:15:13] Donalen: I mean, I, I wouldn't ever say that I would want to forget completely or not ever talk about this stuff that happened to me again, because then it would take away a part of me because that's something that I went through and it's made me a stronger person. It changed who I am. And I think that even though it's something that's really traumatic and quite horrendous, um, it's a part of me now and it's something that I have to deal with.

And so it's something that I, you know, want to talk about and like. So my old therapist used to say to me, it's like having a closet full of stuff. And even though you don't necessarily want to throw away the stuff in the closet, you do want to organize it so that when you open the closet, it's not just pouring out, you know, like you want to have it in a controlled sense.

So like, although these horrible things may have happened to me and I have to stuff it all in the closet sometimes just to be sane, um, it's, you know, it's something that's like, you need to be able to access it because it's not something that you want to forget. Cause that's, it's something that, you know, you want to remember because you don't ever want that to happen again.