Colonization

Historical Trauma

Racism

Helplines

Creative Processing

Poetry

Episode Transcripts

White Supremacy Culture

Other Important Links

Colonization

Colonization

Colonization is an ongoing process which forces people off of their native lands and forces them to live under an external, foreign set of rules, laws, and beliefs. All of the United States is colonized. There are many good resources for understanding how this affects everyone.

The Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium offers a free participatory history lesson called the Alaska Blanket Exercise that helps people in Alaska understand the effects of colonization. Find out more here and listen to the first half of the episode with Jackie Engebretson.

Native Movement is a nonprofit based in Alaska that offers classes on understanding settler colonialism and its lasting effects. They also have a resource page with podcasts, books, articles, and more.

Native Lands is a world map that shows who are the Indigenous people in many parts of the world. Find out whose land you are on then learn more.

If you have other good resources to share, please email Anne at [email protected].

The Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium offers a free participatory history lesson called the Alaska Blanket Exercise that helps people in Alaska understand the effects of colonization. Find out more here and listen to the first half of the episode with Jackie Engebretson.

Native Movement is a nonprofit based in Alaska that offers classes on understanding settler colonialism and its lasting effects. They also have a resource page with podcasts, books, articles, and more.

Native Lands is a world map that shows who are the Indigenous people in many parts of the world. Find out whose land you are on then learn more.

If you have other good resources to share, please email Anne at [email protected].

Historical Trauma

Historical Trauma

Historical trauma is the idea that trauma, such as forced displacement or war, can affect the health of multiple generations not just the ones that experienced the trauma first-hand. The trauma is perpetuated and aggravated by systems of oppression. There's extensive academic research around the lasting effects of historical trauma by both Indigenous and non-indigenous authors. It's also been covered by numerous popular media outlets.

Here are a few links to some useful resources:

Here are a few links to some useful resources:

Collective understanding

Dr. Joseph Gone, a member of the Aaniiih-Gros Ventre tribal nation in Montana and a psychiatrist at Harvard University, writes a lot about historical trauma and healing justice in Indigenous communities. You can read more about his work here.

In a 2019 interview with Mad in America, which is worth a full listen, he said:

Dr. Joseph Gone, a member of the Aaniiih-Gros Ventre tribal nation in Montana and a psychiatrist at Harvard University, writes a lot about historical trauma and healing justice in Indigenous communities. You can read more about his work here.

In a 2019 interview with Mad in America, which is worth a full listen, he said:

|

Historical trauma "recognizes our problems today but anchors their origin in our histories of oppression so we can get out of the paralyzing self-blame narratives. We have to re-socialize a series of issues that have been medicalized for a long time, which in turn has led to individuation where only the individual is the site of therapeutic engagement. With historical trauma, it is about entire communities that have been deliberately impoverished and are in need of desperate remedies. This may look less like healing and more like justice."

|

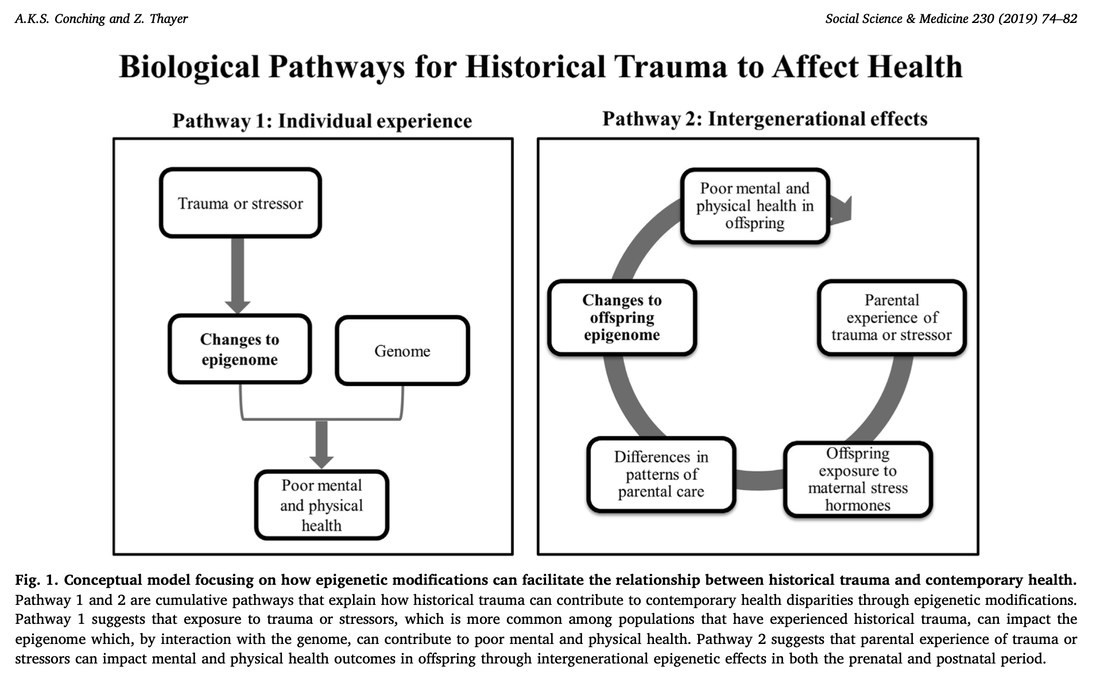

A model to understand the biological effects of historical trauma

Andie Kealohi Sato Conching and Zaneta Thayer wrote a piece in Social Science and Medicine in 2019 that puts forth two different biological pathways for historical trauma to affect the health of multiple generations. The example they provide of a pregnant Native Hawaiian woman in 1848, when Native Hawaiians lost rights to their land, makes it much easier to understand. Here's the full text.

Andie Kealohi Sato Conching and Zaneta Thayer wrote a piece in Social Science and Medicine in 2019 that puts forth two different biological pathways for historical trauma to affect the health of multiple generations. The example they provide of a pregnant Native Hawaiian woman in 1848, when Native Hawaiians lost rights to their land, makes it much easier to understand. Here's the full text.

Healing from historical trauma

This article by Natalie Avalos, PhD explains both colonization and historical trauma and offers a path forward for healing. She writes, "historical trauma has been described as a soul wound because it is experienced as a wounding down to the level of being...it is instigated by a total loss of lifeways, producing deep philosophical disorientation."

Healing requires restoring "healthy relationships to one’s self and members of the larger social body," she writes. "This social body includes the natural world and all living within it, human and other-than-human, such as plants and animals, but also one’s ancestors."

BBC: Can the legacy of trauma be passed down the generations?

This 2019 BBC article gets into details about epigenetics in a pretty accessible way starting with a look at U.S. Civil War veterans. The author details studies done on mice as well as with humans in a way to explore the biological process. Read the full article here.

This article by Natalie Avalos, PhD explains both colonization and historical trauma and offers a path forward for healing. She writes, "historical trauma has been described as a soul wound because it is experienced as a wounding down to the level of being...it is instigated by a total loss of lifeways, producing deep philosophical disorientation."

Healing requires restoring "healthy relationships to one’s self and members of the larger social body," she writes. "This social body includes the natural world and all living within it, human and other-than-human, such as plants and animals, but also one’s ancestors."

BBC: Can the legacy of trauma be passed down the generations?

This 2019 BBC article gets into details about epigenetics in a pretty accessible way starting with a look at U.S. Civil War veterans. The author details studies done on mice as well as with humans in a way to explore the biological process. Read the full article here.

Racism

Racism and mental health

Structural racism in mental health treatment: Oppression and structural racism have a direct impact on mental health, and the mental health system is itself racist and classist. The diagnoses and medications people receive are in part determined by their race and class. Dr. Helena Hansen provides personal examples and delves into her research during this 2021 interview with Mad in America. Listen to it or read the transcript.

Social determinants of mental health: Our mental health is affected by more than just the chemicals in our brains and personal experiences. It's also shaped by the environment around us and our access to resources like food, education, housing, green space, etc. Dr. Ruth Shim talks about this during the episode on racism and mental health. Learn more about her work here and here. Or if you'd rather listen to her speak more, check out her talks on YouTube or check out her interview (and others!) at Unapologetically Black Unicorns.

Looking for books on these topics? Check out The Protest Psychosis by Jonathan Metzl or (Mis)Diagnosed: How Bias Distorts our Perception of Mental Health by Jonathan Foiles.

Social determinants of mental health: Our mental health is affected by more than just the chemicals in our brains and personal experiences. It's also shaped by the environment around us and our access to resources like food, education, housing, green space, etc. Dr. Ruth Shim talks about this during the episode on racism and mental health. Learn more about her work here and here. Or if you'd rather listen to her speak more, check out her talks on YouTube or check out her interview (and others!) at Unapologetically Black Unicorns.

Looking for books on these topics? Check out The Protest Psychosis by Jonathan Metzl or (Mis)Diagnosed: How Bias Distorts our Perception of Mental Health by Jonathan Foiles.

Helplines

Who to call for help

National Suicide Prevention Lifeline - 1-800-273-8255 -- Available 24/7/365

Careline Alaska - 1-877-266-4357 (HELP) -- Available 24/7/365

NAMI (National Alliance on Mental Illness) - Find your local chapter here.

SAMHSA’s National Helpline - 1-800-662-4357 -- For substance misuse treatment referrals

Lines for Life - This service is based in Oregon and offers helplines for specific groups:

Careline Alaska - 1-877-266-4357 (HELP) -- Available 24/7/365

NAMI (National Alliance on Mental Illness) - Find your local chapter here.

SAMHSA’s National Helpline - 1-800-662-4357 -- For substance misuse treatment referrals

Lines for Life - This service is based in Oregon and offers helplines for specific groups:

- Racial Equity Support Line - 503-575-3764

- Military

- Call 888-457-4838 (24/7/365)

Text MIL1 to 839863 Monday-Friday, 2-6pm PT

- Call 888-457-4838 (24/7/365)

- Teens - Talk to teen peer support from 4 - 10 pm PT, adults at other hours

- Call 877-968-8491

Text teen2teen to 839863

- Call 877-968-8491

Creative Processing

Creative processing

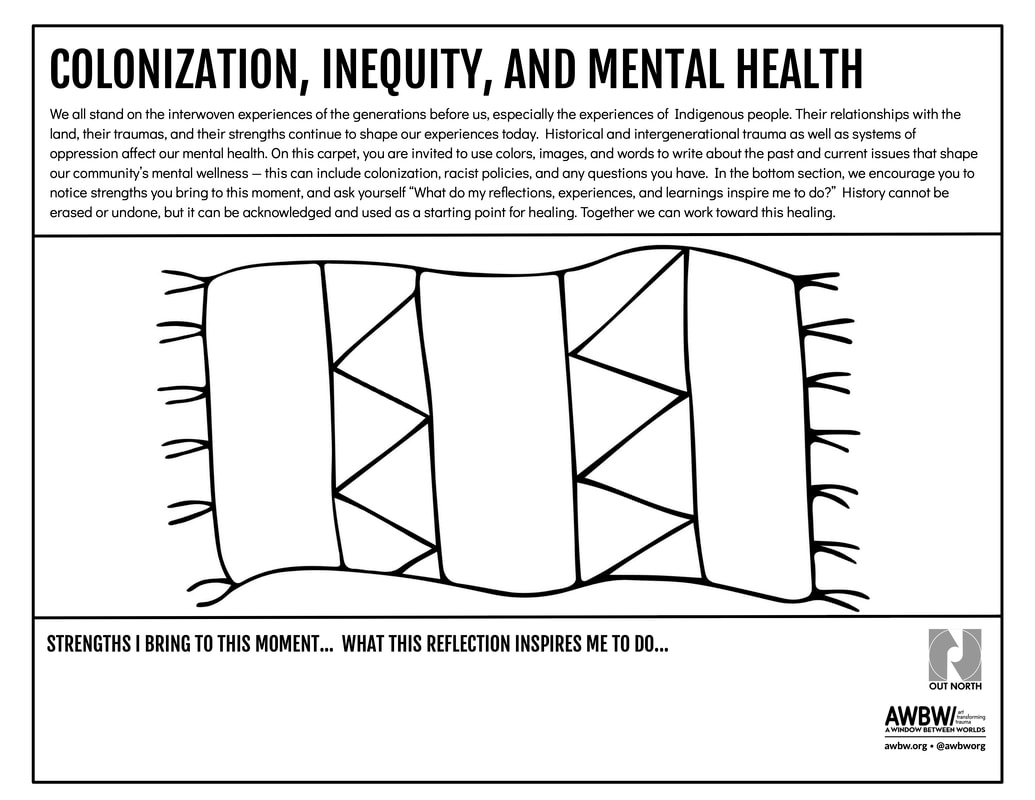

We are all affected by colonization, historical trauma, and systemic oppression and inequities. We cannot disconnect ourselves from the past, present, and future of the lands where we live. And all of that can be a lot to process.

For this exercise you can use any supplies you have, from a scrap of paper and a pen to paints and pastels. You can also download the worksheet below. Using words or images, write down the long-term community factors that affect mental health. This may include effects of colonization or racist policies. Write down any questions you may have, too. You may want to ground yourself before doing this exercise by taking a few deep breaths while thinking about your community’s history.

When you finish, you may want to crush up the paper and throw it or stomp on it. These issues are very emotional and safe physical releases are healthy. Or you may choose to post it somewhere as a reminder of what we need to heal from.

History cannot be undone, but we can acknowledge it and move forward with a focus on equity and healing.

For this exercise you can use any supplies you have, from a scrap of paper and a pen to paints and pastels. You can also download the worksheet below. Using words or images, write down the long-term community factors that affect mental health. This may include effects of colonization or racist policies. Write down any questions you may have, too. You may want to ground yourself before doing this exercise by taking a few deep breaths while thinking about your community’s history.

When you finish, you may want to crush up the paper and throw it or stomp on it. These issues are very emotional and safe physical releases are healthy. Or you may choose to post it somewhere as a reminder of what we need to heal from.

History cannot be undone, but we can acknowledge it and move forward with a focus on equity and healing.

Poetry

Poetry

No Justice George No Peace Breonna (2020)

by M.C. MoHagani Magnetek

Where are you now that George Floyd has died

Are you down and ready to ride

Take no more with your last breath

Let the system burn till there’s nothing left

But the hardcore reality that black lives matter

Water cooler convo filled with chatter

Calling into question your humanity

Like a grudge, Corona got a grip on sanity

Got folks sick tired hot bothered and sad

Everybody and their mama all pissed-off and mad

About a black woman shot and killed in her own house

Don’t act like you don’t know Breonna Taylor is who I’m talking about

So yeah don’t worry about that bucket of water

Remember the centuries of genocide and slaughter

Superiority complex can’t be unlearned

And so what… the roof is on fire. Let it burn

Give them no choice

But to listen and respect our voice

Get your hands out my pockets!

No Means No We Said Stop It!

Murderers getting paid on administrative leave

Promoted for using their knees

To choke hope out of the ppl

All lives matter, C’mon mayne… this shit ain’t equal

Tell me what’s making a difference supposed to look like

Match struck fireworks in broad daylight

No longer satiated

Refused to be placated

Until the killing of our people cease

If there’s no Justice for George & Breonna, there will be no PEACE.

by M.C. MoHagani Magnetek

Where are you now that George Floyd has died

Are you down and ready to ride

Take no more with your last breath

Let the system burn till there’s nothing left

But the hardcore reality that black lives matter

Water cooler convo filled with chatter

Calling into question your humanity

Like a grudge, Corona got a grip on sanity

Got folks sick tired hot bothered and sad

Everybody and their mama all pissed-off and mad

About a black woman shot and killed in her own house

Don’t act like you don’t know Breonna Taylor is who I’m talking about

So yeah don’t worry about that bucket of water

Remember the centuries of genocide and slaughter

Superiority complex can’t be unlearned

And so what… the roof is on fire. Let it burn

Give them no choice

But to listen and respect our voice

Get your hands out my pockets!

No Means No We Said Stop It!

Murderers getting paid on administrative leave

Promoted for using their knees

To choke hope out of the ppl

All lives matter, C’mon mayne… this shit ain’t equal

Tell me what’s making a difference supposed to look like

Match struck fireworks in broad daylight

No longer satiated

Refused to be placated

Until the killing of our people cease

If there’s no Justice for George & Breonna, there will be no PEACE.

Episode Transcripts

Colonization & Oppression

Ways to Decolonize

Racism

Colonization & Oppression

Colonization and Oppression - Part One

[00:00:00] Anne: Welcome to Mental Health Mosaics, an exploration of mental health from Out North, which is located on the unceded traditional lands of the Dena'ina People in Anchorage, Alaska. I'm Anne Hillman.

When we talk about mental health we often focus on what's happening to each of us as individuals and how we're dealing with life right now. But humans don't exist in bubbles. What happened in our community's past and what's currently happening, including racism and inequity, affects all of us and our mental health. We can't ignore it. So for the next two episodes we're going to focus on colonization, white supremacist culture, and mental health. Yes -- this is going to be heavy and yes, you are probably going to be uncomfortable.

This episode is kind of a primer -- we'll jump into the basics of how colonization in Alaska is having a long-term impact on mental health, why teaching that history is so important, and have a more philosophical conversation about understanding what historical trauma is.

If you are well-versed in Alaska Native history and understand, especially through personal experience, the effects of intentional cultural destruction, this episode is full of triggers and you may want to skip it. But we don't just talk about trauma, we also talk about strength because every culture and every community has both. If you are a non-Indigenous person, especially one who lives in Alaska, please keep listening. This is just the start of what we all need to know when living on Indigenous lands whether you care about mental health or not. So, without further ado, please meet Jackie, who was willing to provide a pretty intense history lesson.

[00:01:50] Jackie: My name is Jackie Engebretson and my family is from Gulkana, which is in the Copper River region here in Alaska and I'm Ahtna Athabaskan, although I grew up in both Copper Center and Valdez. Currently, I am a senior program manager in the behavioral health department at the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium.

[00:02:09] Anne: Well, thank you so much for joining us today. So I'd love to start with conization. What does that mean? And what does that mean in Alaska context?

[00:02:18] Jackie: Colonization would be when an outside country/entity comes into another space and takes over in a sense. They start occupying the land as if it was their own. They start making their own rules and laws as if they were the like supreme leaders of that space. Most often that means they are supplanting local populations. So in the state of Alaska there've been many different colonizing forces. Initially the colonizers would be the Russians, particularly in a Western Alaska and in the Aleutians.

Other areas of Alaska did not have as much of a Russian influence, so they had people like missionaries come in, people like the U. S. army come in, and those were their primary colonizers.

So in those instances, like been particularly areas that were colonized by Russians, you saw Russian orthodoxy takeover. You saw Russian culture, Russian language become more predominant. And then in areas where Christian missionaries came in. You saw Christian churches, Christian schools, and rules centered around Christianity instead of the local indigenous populations.

[00:03:38] Anne: And instead of around local and Indigenous belief systems?

[00:03:40] Jackie: Correct, yes.

[00:03:42] Anne: Why is that damaging?

[00:03:45] Jackie: So you have a group of people in the state of Alaska, that'd be Alaska Nativesm who have occupied the land for tens of thousands of years. And they have used the land in ways that feed their family, that nourish their soul, and it's their home.

And all of a sudden you have these people coming in who have a different viewpoint when it comes to how you use land. With Russians, they did a lot of trapping and hunting and over trapped and over hunted resources that Alaska Native people have been using for many, many years without impacting the animal populations.

Resources that were once available are no longer available. You have people occupying spaces that were historically yours. That could be places where your family used to gather food. That could be places where your family used to go to practice spiritual practices. That could be places where your family has just traditionally occupied and all of a sudden there are Russians or Americans living in this land and telling you that you can no longer use it. And it can impact the way you hunt and just it impacts all ranges of your life.

[00:05:03] Anne: And does it impact mental health?

[00:05:05] Jackie: Yes, it can absolutely impact mental health. That's some of the things that we see more long-term here in Alaska.

Particularly as colonization continues. There's like restrictions on how you can hunt, when you can hunt, who else is allowed to hunt, and who else is on your land. They're telling you what you must believe. When your whole way of life is just shifted that way, you lose many different protective factors. And so protective factors are things that kind of keep you mentally and physically safe. So with Alaska Native people -- with people in general, to be honest, this is not just a Native thing -- but identity is a huge part of what helps people feel more rooted in who they are.

And in the United States, there is a general lack of identity, not just with Alaska Native people, not just with Indigenous people. There are a large number of people in this country who just don't have that sense of identity that maybe previous generations would have or maybe other groups throughout the world do have.

[00:06:11] Anne: Just because in the United States, there's is this giant push towards assimilation, and we are all the same, and there is a dominant culture and, and it sort of eliminates our roots and our connections.

[00:06:23] Jackie: Absolutely. And so that's especially true here in Alaska with Alaska Native people. The long-term impacts of colonization might include things like I mentioned, not being able to hunt. So for a lot of Alaska Native men, for instance they had roles that they were expected to fulfill including hunting and gathering and things like that. And now those roles are limited and they no longer have the same ability to do things that they might have previously.

Historically, my people were semi-nomadic so they would move from camp to camp depending on the season. They'd have fish camp and they'd have a hunting camp and they'd have places they'd go to pick berries and things like that. And that was down to the family level.

But after colonization, there was a huge push for families to stay in one spot so that the kids could go to school. “This is in the best interest of your kids. And if you want them to have a good education and a good life, then you need to stay here in this village and your kids need to go to school. They need to go to school following this schedule and that schedule doesn't follow subsistence hunting.

It doesn't follow it -- doesn't follow anything. It follows this arbitrary date that the U.S. government or the state government has told kids that they must be in school. So things like that. You're not following your own traditional and cultural practice. Instead, you're doing what is expected of you by the U.S. government.

[00:07:52] Anne: And at the same time, there's still a practical need to hunt and gather in rural Alaska to get the food and nutrition people need to survive.

[00:08:02] Jackie: We know what naturally grows in Alaska and how we receive our nutrients. You know, traditional Alaska Native diets fulfilled all the nutritional needs. And without eating all of those foods, you're not getting the same needs and instead you need to supplement them with things that you might get from the grocery store. And the items that you might get to supplement your nutritional needs from the grocery store might be extremely expensive because it needs to be shipped up from the United States.

You might have to take vitamins and things like that. So I think from a practical purpose, it's something that's still necessary today. There’s a nutritional basis. And then just the spiritual connectedness that comes from hunting and gathering and being connected to the land and being part of and having a relationship with the land that you have for tens of thousands of years is also still important.

[00:08:56] Anne: And that, again, brings us back to mental health and how these spiritual connections keep us well. I mean, physically well, but also well as whole people. You mentioned earlier, it's not just restrictions on land. Just limiting of land use and movement that happened through colonization, but you also mentioned that churches and missionaries came in.

How did that affect the Indigenous peoples of Alaska?

[00:09:30] Jackie: Yeah, I think the most notable example and one that's probably most relevant to the discussion today would be boarding schools. So throughout the state there were -- and this is honestly something that's an international thing is not something that just happened here in Alaska. We've seen a lot of talk about it in the news recently, due to mass graves being uncovered in Canada. Mass unmarked graves from children in Canada, children that were never returned home.

So the boarding schools were set up to assimilate Indigenous youth. And there was this mentality at the time where the idea was to “save the man and kill the Indian.”

So you save the man by sending them to school, to this boarding school, away from their family, away from their community. And you kill the Indian by not allowing them to speak their language, by not allowing them to be raised by their community and not practice their spiritual practices, their traditional practices, not allowing them to sing their songs, not allowing them to dance.

And by the time you're done with them with them, by the time they were done with boarding school, if they survived, they would be sent back to their communities and no longer feel a sense of identity. Or feel very disconnected from their identity. Not only from their identity, but from their family, from their mom, their dad, from their community.

And many people who go into boarding school just never returned to their community, whether it be because they passed away or because they just no longer felt like they were a part of their community. One of the ways that they would assimilate was by not allowing them to speak their language and children would be punished.

I've heard many stories from elders and I think a lot of other people have heard other stories as well. Punishment, like restricting food, not allowing them to eat. Physical punishment, whether it be spanking, beating, a lot of really terrible, terrible things happened to children in boarding schools.

[00:11:33] Anne: And just a side note here -- the boarding schools in Alaska were started by missionaries. By the early 20th century, they were run by the federal government. It was the U.S. government's policy to take children away from their families and sometimes send them to the other side of the continent. And all of this led to really negative long-term consequences that we still feel today. This isn't just a history lesson. Boarding schools have created persistent, intergenerational trauma. Back to Jackie.

[00:12:06] Jackie: Because they weren't raised by their families, a lot of youth who went through boarding schools didn't have a model of what parenting should look like. So when they grew up to be adults, they had hard time parenting themselves.

They might not have been the healthiest parents. They might not have been the most present parents. It had a lot of long-term impacts on parenting. It had a lot of long-term impacts on people's mental health and their physical health. We know that when people experience Adverse Childhood Experiences that there's long-term impacts to that. It could affect your physical health. It's higher rates of diabetes, higher rates of obesity. It can impact their mental health. They're more likely to interact with the criminal justice system. All of those, I mean like many more things as well.

[00:12:56] Anne: Use substances?

[00:12:57] Jackie: Use substances. Exactly. Exactly. Substance use rates are also very, very high for people who have high ACE scores. Going to a boarding school is just a number of ACEs that add on, with an added aspect of like racism in it as well.

[00:13:16] Anne: Talk more about the aspect of racism. I mean the obvious eliminate who you are and eliminate cultures.

[00:13:24] Jackie: Yeah. So all of this was rooted in the idea, like I mentioned of kill the Indian, save the man. So the idea is that since colonization here in the United States and worldwide as well, is that people of non-European descent are lesser than. They're like lesser than human often, but they're certainly lesser than their white counterparts. So there was this idea that American Indians and Alaska Natives and other populations worldwide were savage or that they were uncivilized or that they were backwards.

And just this idea that they were not equal and that they needed to change. And that colonization was to save them and was a good thing for them. And that European people were supreme and were just more civilized and therefore were doing you a favor. So there was a racial component in the boarding schools because they wanted Native youth to be more like white people.

[00:14:31] Anne: Thinking about this intentional move to cut people off from their families, to cut people off from their culture, to try to make them into someone else. I feel like that hasn't stopped to this day, so how does that relate to behavioral health? Like why do you as a behavioral health organization work to make sure that people understand the complexities of these issues?

[00:15:02] Jackie: That's a great question. I can use myself as an example if that helps.

The reason why this kind of work is really important to me is because of my own kind of lived experiences and things that I've seen in my family, friends, my community. But talking about me specifically since it's my story and my place to tell. I grew up in a very complicated family system. And I know that we all loved each other, but there was trauma that was carried over through generations.

My parents experienced trauma from their parents and my grandparents experienced trauma from their parents. I honestly don't know how far back it goes, but I would imagine it goes back pretty far.

And I think some of it is rooted in some of the things that happen to our community and perhaps how people were treated many, many generations ago that still shows up today. And so I grew up thinking that there was something wrong with me, thinking that there was something wrong with my family and that there was something wrong with my community. Some of the challenges that I had in my own life -- I struggled with depression. I still do. And then eventually I struggled with substance use, and I thought that was because I was Native. And I thought it was because there was something wrong with my family. And I thought that it was just kind of my destiny and like it was going to happen. And it was inevitable.

[00:16:28] Anne: Just because you were Native?

[00:16:30] Jackie: Yeah, because the messages I received, I think from everybody. Everybody gave you these messages. Um, certainly when I was in school, I was a high achiever. I didn't have a lot of Native friends when I was in high school. And I would hear people say things about Natives and I'd be like, “Oh, they're not talking about me though.”

It like took until I had become an adult to really understand. It's like, well, even if they weren't talking about me, they were definitely talking about some of my cousins. Or they're definitely talking about my auntie or my uncle. So yes, they were talking about me, and I just thought I was like one of the good ones when I was in high school or something. And then I had this like crashing reality when I was on my own and an adult and trying to just deal with all these complicated things that I had experienced in life and wondering what's wrong with me. And I know that this is true for other people all over the place.

And I know that there are still people who are living in these really complicated patterns in their life because of historical trauma, because of intergenerational trauma. Who are internalizing that and thinking that there's something wrong with them or maybe thinking that there's something wrong with everybody around them. And not understanding that there's been a lot of things that have happened to us as a people, as family systems that are just really difficult to overcome. And unless you have access to resources and unless you're aware of what's going on, you're not going to be able to get the help. You're not going to, or you might not even want to. And if you think that there's something wrong with you, you're going to think there's probably something wrong with going to therapy or there's probably something wrong with going to treatment. Or there's something wrong with taking medications that can help manage your mental health.

So there's like all these really complex thought processes that go on with people. And the added like racism and stigma associated with a lot of the things we talked about, substance use, mental health, being involved in the criminal justice system, that just like all these different barriers that make people not want to access care.

So the reason why we at ANTHC decided to share the Alaska Blanket Exercise widely is because we wanted providers to understand, “Hey, your patient, isn't just not showing up or like not taking their medication because they don't want to, or because they're willfully being ignorant they're willfully being bad patients. It's because they have a lot of things going on in their lives and they're doing the best that they can to show up. And you need to understand this. You need to understand their traumas.”

It's to help Alaska Native people understand, "Hey, this is, this might be why your family is the way that they are, and there's nothing wrong with you. It's just, there's, there's been a lot that has happened." It think it just helps people be more compassionate for others and for themselves.

[00:19:33] Anne: Explain what this Blanket Exercise is.

[00:19:40] Jackie: Sure. So the Alaska Blanket Exercise is a participatory history lesson. We initially partnered with a Canadian organization called Kairos. They do a version called the Kairos Blanket Exercise in Canada. And so their exercises focused on First Nations experiences. They came to Alaska a couple of years ago and shared it with us. And the people that participated in that initial one were just so impressed with it that they wanted to bring it to Alaska.

So it is an adaptation of a Canadian exercise. The exercise itself has two parts to it. It has a history lesson and then a talking circle. For the history lesson we have people set up in a circle, a large circle of chairs around blankets. These blankets are spread out across the floor in between all the chairs, and we have participants step onto the blankets and step into the role of Alaska Native people.

When they're stepping onto the blankets, they're stepping onto traditional Alaska Native lands, which is all of Alaska. So at the beginning of the exercise, there are a lot of people on these blankets. There's a lot of blankets spread out all throughout. We also have two narrators who read through the Alaska Native history timeline.

And as they go through the timeline several things happen. The land gets smaller and the number of participants on the land, the number of Alaska Native people also gets smaller. So the things that caused the, the decrease in land or the decrease in people, are all related to actual historical events from the Alaska Native history to represent the loss of both land and people and also the relationship between Alaska Native people and the land.

Anne: And then as people go through the simulation, then what?

Jackie: So the experience itself, the history lesson portion, can be kind of intense. It's very emotional for a lot of people. We also have what we call scrolls and they're quotes from either Alaska Natives or political figures in the state of Alaska.

Some of them are really, really tough. There’s one quote in particular from a man who survived the internment camps.

[00:22:23] Anne: Jackie's talking about the internment camps for the Unangax̂ people during World War II. The US government forced the Unangax̂ to leave the Aleutians in 1942 and live in places like old fish canneries in Southeast Alaska for three years. Conditions were very, very harsh. Back to Jackie.

[00:22:42] Jackie: And he was talking about his baby brother who got double pneumonia and then died and how it was the tiniest coffin he had ever seen. The first time I did the exercise myself, I volunteered to read a quote and that's the one I got. And it was just, it was so hard to make it through and it.

That's only a small, small, small percentage of the amount of pain that family felt, that community felt for that tiny coffin. So it's a very emotional experience. I think it's especially emotional for a lot of Alaska Native participants because even if it's not directly related to an experience they had, or that one that their family might've had, they can relate to it.

There's a lot of things in there that make people think, “Oh, I wonder if that happened in my community.” So it can be quite, quite emotional. We do, I want to mention, highlight a lot of strengths in it. It’s really, truly amazing to see what people focus on. We’ve had peoples say they felt really uplifted at the end.

And that's great. Cause we try to have equal balance. Cause there have been a lot of really great things that have happened. Like Elizabeth Peratrovich, for instance, she's a great example to lift and shine, uplift and shine, or the Alaska Native Brotherhood or the Sobriety Movement. There's a lot of really great things to leave with as well. We don't try to traumatize people and then leave them. We also try to highlight a lot of the strengths and the people who are learning their culture again and who are learning their language and all of the efforts to take people are taking to combat colonization in their own personal lives or in their community.

[00:24:29] Anne: So it's both teaching about the pain so that people understand where Alaska Native communities are coming from and where we as a state are coming from, as well as highlighting that actually there's boundless resilience and boundless strength, and always has been.

[00:24:48] Jackie: Yes, absolutely. That is something that we always try to highlight is the resilience. Despite all of these things that have happened to Alaska Native people, we're still here. And we're still here in great, great numbers, and we're doing a lot of really great things in our communities and in our families. And it's important to highlight those things. It's important not to just always talk about the high rates of this or the high rates of that and this community is struggling with this. There's a lot of really great things happening in Alaska Native communities, too.

Also, another component that we didn't really touch on at all was the talking circle. So that can be another way to get people engaged in conversation. And that's part of every exercise. Our talking circle is open forum and people can talk about whatever they want or they can not talk if they don't want to.

I think that really adds to the experience. We ask that people respect each other's privacy, and not talk about it afterwards. What's talked about in the circle, stays in the circle. From our evaluations, we know that the talking circle at the end has almost as much impact on people as the actual exercise itself.

It's a time for people to kind of provide their own testimony and talk about their own experiences and for people to be vulnerable, if that's what they feel comfortable doing.

[00:26:19] Anne: I could see that being really powerful and scary experience in a lot of ways.

[00:26:27] Jackie: Absolutely.

[00:26:30] Anne: With some of the providers and behavioral health care folks that you work with, how has the Blanket Exercise changed the way they practice or the questions that they might ask to help someone along a healing process?

[00:26:50] Jackie: I think it gives people like a sense of what questions am I not asking? What information do I not have? How can I support people better? And how can I connect with them? We haven't really done any long-term outcome evaluation. That's one of the things we're really interested in doing, because we want to know how people are doing it are how people are incorporating it into their work.

But apart from just what we hear offhand, we don't have any solid answers for that yet.

[00:27:24] Anne: Jackie has big dreams for the Blanket Exercise. She wants to create versions for young people and to bring it to schools. She plans to expand the number of facilitators so that all community organizations, including private companies, can participate in the experience because it can make a difference for people who aren't involved with mental health, too. For example, she said that after managers of a grocery chain with stores in rural Alaska participated, it changed how they interacted with employees and customers. Because of COVID-19, ANTHC is currently working on creating a virtual adaptation of the Blanket Exercise. They'll start offering it for free to everyone in early 2022.

[00:28:08] Anne: What Jackie shared was only a brief piece of Alaska's history and how that history still affects Alaska communities today. It's a lot to sit with. So before we delve even deeper into ways to think about historical trauma and the effects of colonization, I'd like to invite you to take a moment to think about these issues on a more personal level and to ground yourself. If you are in a safe space to do so, maybe close your eyes, take a few deep breaths, and think about where you are and who was on this land before you. You could even consider pausing this podcast and jotting down a few thoughts, feelings, or questions that Jackie's interview brings up for you. Take a moment to reflect and then I'll introduce you to Meda.

[00:29:08] Anne: My next guest is Meda DeWitt, a traditional healer and researcher, who I asked to help me understand historical trauma more broadly and how it shapes communities.

[00:29:19] Meda: [Greeting in Tlingit is not transcribed.] My English name is Meda Witt. My Tlingit names are Tśa Tsée Naakw and Khaat kłaat, adopted Iñupiaq name is Tigigalook, and adopted Northern Cree name is Boss Eagle Spirit Woman. I live Dena’ina lands, that’s Anchorage area. I'm here with my fiancé, Chris Paoli. He and I combined have a total of eight children, seven still at home, and it's beautiful to be here.

[00:30:09] Anne: Meda is also a member of the Mental Health Mosaics Advisory Board. She says Tlingit people have a culture of wellness that stems back at least 20,000 years.

[00:30:21] Meda: So everything is built around best practices that've been tested out and observed over thousands of years. And some people are like, “Oh, 10,000 years.” It's like, no, like 20 plus thousand years. Much, much longer than the anthropologists [say]. Every time they dig something up and they find like, “Oh, we found something 14,000 years old.” my auntie's like, “Well, grandma always said that they just had to dig deeper.”

So our cultural stories are much older and we have a long cultural memory that's a living memory. So they impart these concepts and culture and experience almost in a way that is relatable in a first person. Whereas in the Western systems, it's historical and it's a long time ago. And there's a disconnect.

[00:31:15] Anne: So we need to keep this disconnect in mind when thinking about history.

[00:31:20] Meda: The concept of history is different in the two groups, right? So we're working within a trade barter language, which is English. And English is limited. As you know, it's comprised of multiple different languages and it's heart and soul is based on economic exchange and barter.

So we think that we're speaking about the same language or same words and same concepts, when reality is many times we aren't. So people will be in conversations or they'll have disagreements, and it comes down to the fact that they don't have a shared understanding of what's being said.

So historical trauma is a massive occurrence that happened to a family or a cultural group, a group of people. And in the Western context, it means it happened a long time ago. In more Indigenous and familial structured communities historical trauma is something that has happened to a group of people that has influenced their culture and is a part of who they are.

[00:32:30] Anne: Trauma in one generation can also affect people in future generations by changing the expression of their genes. We are not going to go into the science of epigenetics right now, though you can find links to research on the topic on our website. But Meda and many others say that this idea—that trauma affects us generations down the line—has always been a known truth in many Indigenous cultures. It's called blood memory.

[00:33:00] Meda: We had certain protocols of how to behave, like when you're pregnant. And you don't want to stress the mom out because it affect the behavior of the child after it's born. So knowing that trauma has effect on humans in utero. And we also knew that if there was something that happened in the family line that it could manifest in further generations down.

[00:33:27] Anne: So a quick recap: Historical trauma may have happened generations ago, but we aren't detached from those events and their aftereffects. History reverberates through and shapes life today, it shapes families, and it effects all aspects of health. And it’s not just trauma that passes from generation to generation. It's strength. Meda says we need to think about how we frame the stories we tell.

[00:33:59] Meda: That's like Alaska Natives and American Indians. When we have the capacity to have self-governance and internal sovereignty and sovereignty as a group to make our own choices and to define who we are and how we move through this world—then those stories transition from a painful story of burden into an experience that we share, and then our resilience is our story of strength.

So for instance we have a lot of migration stories. And traditionally with the climate has changed several times, but because of our carbon use and the way that we've been using fossil fuels, it's expedited in how fast it's coming on. But there are other times in our history—we have oral histories. And our oral histories are passed down through story keepers and it has to be done in a very specific way.

And even in inflections of the voice. You have to learn it very specifically to tell these stories and to be considered a traditional story keeper. The Tlingit people used to be interior Canada, and there was melting of the glaciers so they had to go to the coast because the food systems were crashing.

And it was very traumatic. People were dying and they were starving and there was a sickness. And they had to make the choice to leave a space that they loved because they couldn't sustain in those spaces anymore. And so that choice of being able to move, and that process of going through the motions of problem solving and courage and strength and then making it to the coast, that's a part of our traditional resiliency stories—the coming under the glaciers.

Resilience is baked in to the culture. Resilience is baked into these stories and spirit and the way of being connected to the land and to Creator and each other. And those are fundamentally the most important success factors in any group of people that you can have, that connectivity.

[00:36:21] Anne: So where do we go from here? How do we heal from traumas so they don't keep affecting generation after generation? Meda is going to talk a lot more about this in a later episode that specifically focuses on Alaska Native Traditional Healing, a topic that's useful for everyone. But in the meantime, she offers this starting place—acknowledge what happened in the past. She says even this step is going to take time and won't always go smoothly.

Meda: We're going to be wonky and imperfect, like a ragtag band of rebels who made it through several hundreds of years of violence. Right?

And so now it's time to acknowledge what happened and rebuild. And there's definitely people who were privileged and benefited from the colonization. And that's part of this challenge. I challenge people to acknowledge this history and everybody has work to do. So if it's uncomfortable for you to acknowledge what happened and speak about it and feel like it's a responsibility to shift the narrative, then that's where people need to work.

Like step into that space that's uncomfortable and help to elevate this collective narrative. Gosh, you know, like let's just tell the truth.

Anne: It's really, really important to note here that acknowledging the trauma caused by colonization, boarding schools, and other injustices is just one part of the healing process. We also need to acknowledge and change the current systems of oppression that have led to severe inequities in our society, all of which affect everyone's mental health. We're going to discuss that with much more depth in our next episode including during a conversation with Melody Li, a queer therapist of color who is a colony-born migrant from Hong Kong.

[00:38:33] Melody: In the work that I do, I often start with sharing that colonialism, capitalism and white cis-hetero patriarchal hegemony, or domination, are at the root of mental and relational distress. This is very different from what the so-called modern mental health field typically shares. We are taught that mental distress comes from maybe childhood trauma, which is true. From interpersonal conflict, which is true. Or simply arises within the individual on a brain chemistry level, on a neurological level. All of those are true, except it doesn't address the context.

The context in which these distresses are occurring and how colonialism, capitalism, white cis-hetero, patriarchy of course, disproportionately impacts marginalized identities, Black, Indigenous, and People of Color, Two Spirit LGBTQ+ communities, neurodivergent and disabled communities. There are multiple added layers of mental and relational distress when we look at things from a historical, intergenerational and perpetual perspective.

So when we don't intentionally include and bring to light and even focus on how these forces impact our mental and relational wellness then we are perpetuating them within the mental health field. And I think one danger of the practice of the mental health industrial complex is the pathologizing, so diagnosing, and also individualizing these distresses. Saying there's something wrong with this person. Let me put a diagnosis on this person, and offer this person a treatment.

But if these distresses are connected to the systemic and institutional oppressions or violences, then no amount of pathology or individualized treatment is going to help. And that is where we are now.

[00:41:25] Anne: And that is all a lot to take in. This is another good time to ground yourself by taking a few deep breaths, noticing your surroundings, or writing down some reactions or questions. Here's a key takeaway I'd like you to carry into your day: Think about mental health in the context of the larger picture. It's tied to history, land, and systems of oppression. Sometimes we feel alone, but our experiences are connected. Please hold onto those thoughts as we explore these issues more in future episodes.

My thanks go to Meda DeWitt, Cathy Salser, and Erin Willihan for reviewing the episode. Susy Buchanan is editing this project. Aria Phillips wrote our theme music. Dave Waldron is the audio engineer. I'm getting guidance from Jason Lessard at NAMI-Anchorage and from the Mental Health Mosaics Advisory Board -- Cassandra Debaets, Dash Togi, Dana Hilbish, Erica Khan, M.C. MoHagani Magnetek, and Meda DeWitt.

You can find more materials on this subject and other tools for processing your thoughts at mentalhealthmosaics.org. Please rate this podcast to help others find it and share links with everyone you know. I'm Anne Hillman. Thank you for listening.

[00:00:00] Anne: Welcome to Mental Health Mosaics, an exploration of mental health from Out North, which is located on the unceded traditional lands of the Dena'ina People in Anchorage, Alaska. I'm Anne Hillman.

When we talk about mental health we often focus on what's happening to each of us as individuals and how we're dealing with life right now. But humans don't exist in bubbles. What happened in our community's past and what's currently happening, including racism and inequity, affects all of us and our mental health. We can't ignore it. So for the next two episodes we're going to focus on colonization, white supremacist culture, and mental health. Yes -- this is going to be heavy and yes, you are probably going to be uncomfortable.

This episode is kind of a primer -- we'll jump into the basics of how colonization in Alaska is having a long-term impact on mental health, why teaching that history is so important, and have a more philosophical conversation about understanding what historical trauma is.

If you are well-versed in Alaska Native history and understand, especially through personal experience, the effects of intentional cultural destruction, this episode is full of triggers and you may want to skip it. But we don't just talk about trauma, we also talk about strength because every culture and every community has both. If you are a non-Indigenous person, especially one who lives in Alaska, please keep listening. This is just the start of what we all need to know when living on Indigenous lands whether you care about mental health or not. So, without further ado, please meet Jackie, who was willing to provide a pretty intense history lesson.

[00:01:50] Jackie: My name is Jackie Engebretson and my family is from Gulkana, which is in the Copper River region here in Alaska and I'm Ahtna Athabaskan, although I grew up in both Copper Center and Valdez. Currently, I am a senior program manager in the behavioral health department at the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium.

[00:02:09] Anne: Well, thank you so much for joining us today. So I'd love to start with conization. What does that mean? And what does that mean in Alaska context?

[00:02:18] Jackie: Colonization would be when an outside country/entity comes into another space and takes over in a sense. They start occupying the land as if it was their own. They start making their own rules and laws as if they were the like supreme leaders of that space. Most often that means they are supplanting local populations. So in the state of Alaska there've been many different colonizing forces. Initially the colonizers would be the Russians, particularly in a Western Alaska and in the Aleutians.

Other areas of Alaska did not have as much of a Russian influence, so they had people like missionaries come in, people like the U. S. army come in, and those were their primary colonizers.

So in those instances, like been particularly areas that were colonized by Russians, you saw Russian orthodoxy takeover. You saw Russian culture, Russian language become more predominant. And then in areas where Christian missionaries came in. You saw Christian churches, Christian schools, and rules centered around Christianity instead of the local indigenous populations.

[00:03:38] Anne: And instead of around local and Indigenous belief systems?

[00:03:40] Jackie: Correct, yes.

[00:03:42] Anne: Why is that damaging?

[00:03:45] Jackie: So you have a group of people in the state of Alaska, that'd be Alaska Nativesm who have occupied the land for tens of thousands of years. And they have used the land in ways that feed their family, that nourish their soul, and it's their home.

And all of a sudden you have these people coming in who have a different viewpoint when it comes to how you use land. With Russians, they did a lot of trapping and hunting and over trapped and over hunted resources that Alaska Native people have been using for many, many years without impacting the animal populations.

Resources that were once available are no longer available. You have people occupying spaces that were historically yours. That could be places where your family used to gather food. That could be places where your family used to go to practice spiritual practices. That could be places where your family has just traditionally occupied and all of a sudden there are Russians or Americans living in this land and telling you that you can no longer use it. And it can impact the way you hunt and just it impacts all ranges of your life.

[00:05:03] Anne: And does it impact mental health?

[00:05:05] Jackie: Yes, it can absolutely impact mental health. That's some of the things that we see more long-term here in Alaska.

Particularly as colonization continues. There's like restrictions on how you can hunt, when you can hunt, who else is allowed to hunt, and who else is on your land. They're telling you what you must believe. When your whole way of life is just shifted that way, you lose many different protective factors. And so protective factors are things that kind of keep you mentally and physically safe. So with Alaska Native people -- with people in general, to be honest, this is not just a Native thing -- but identity is a huge part of what helps people feel more rooted in who they are.

And in the United States, there is a general lack of identity, not just with Alaska Native people, not just with Indigenous people. There are a large number of people in this country who just don't have that sense of identity that maybe previous generations would have or maybe other groups throughout the world do have.

[00:06:11] Anne: Just because in the United States, there's is this giant push towards assimilation, and we are all the same, and there is a dominant culture and, and it sort of eliminates our roots and our connections.

[00:06:23] Jackie: Absolutely. And so that's especially true here in Alaska with Alaska Native people. The long-term impacts of colonization might include things like I mentioned, not being able to hunt. So for a lot of Alaska Native men, for instance they had roles that they were expected to fulfill including hunting and gathering and things like that. And now those roles are limited and they no longer have the same ability to do things that they might have previously.

Historically, my people were semi-nomadic so they would move from camp to camp depending on the season. They'd have fish camp and they'd have a hunting camp and they'd have places they'd go to pick berries and things like that. And that was down to the family level.

But after colonization, there was a huge push for families to stay in one spot so that the kids could go to school. “This is in the best interest of your kids. And if you want them to have a good education and a good life, then you need to stay here in this village and your kids need to go to school. They need to go to school following this schedule and that schedule doesn't follow subsistence hunting.

It doesn't follow it -- doesn't follow anything. It follows this arbitrary date that the U.S. government or the state government has told kids that they must be in school. So things like that. You're not following your own traditional and cultural practice. Instead, you're doing what is expected of you by the U.S. government.

[00:07:52] Anne: And at the same time, there's still a practical need to hunt and gather in rural Alaska to get the food and nutrition people need to survive.

[00:08:02] Jackie: We know what naturally grows in Alaska and how we receive our nutrients. You know, traditional Alaska Native diets fulfilled all the nutritional needs. And without eating all of those foods, you're not getting the same needs and instead you need to supplement them with things that you might get from the grocery store. And the items that you might get to supplement your nutritional needs from the grocery store might be extremely expensive because it needs to be shipped up from the United States.

You might have to take vitamins and things like that. So I think from a practical purpose, it's something that's still necessary today. There’s a nutritional basis. And then just the spiritual connectedness that comes from hunting and gathering and being connected to the land and being part of and having a relationship with the land that you have for tens of thousands of years is also still important.

[00:08:56] Anne: And that, again, brings us back to mental health and how these spiritual connections keep us well. I mean, physically well, but also well as whole people. You mentioned earlier, it's not just restrictions on land. Just limiting of land use and movement that happened through colonization, but you also mentioned that churches and missionaries came in.

How did that affect the Indigenous peoples of Alaska?

[00:09:30] Jackie: Yeah, I think the most notable example and one that's probably most relevant to the discussion today would be boarding schools. So throughout the state there were -- and this is honestly something that's an international thing is not something that just happened here in Alaska. We've seen a lot of talk about it in the news recently, due to mass graves being uncovered in Canada. Mass unmarked graves from children in Canada, children that were never returned home.

So the boarding schools were set up to assimilate Indigenous youth. And there was this mentality at the time where the idea was to “save the man and kill the Indian.”

So you save the man by sending them to school, to this boarding school, away from their family, away from their community. And you kill the Indian by not allowing them to speak their language, by not allowing them to be raised by their community and not practice their spiritual practices, their traditional practices, not allowing them to sing their songs, not allowing them to dance.

And by the time you're done with them with them, by the time they were done with boarding school, if they survived, they would be sent back to their communities and no longer feel a sense of identity. Or feel very disconnected from their identity. Not only from their identity, but from their family, from their mom, their dad, from their community.

And many people who go into boarding school just never returned to their community, whether it be because they passed away or because they just no longer felt like they were a part of their community. One of the ways that they would assimilate was by not allowing them to speak their language and children would be punished.

I've heard many stories from elders and I think a lot of other people have heard other stories as well. Punishment, like restricting food, not allowing them to eat. Physical punishment, whether it be spanking, beating, a lot of really terrible, terrible things happened to children in boarding schools.

[00:11:33] Anne: And just a side note here -- the boarding schools in Alaska were started by missionaries. By the early 20th century, they were run by the federal government. It was the U.S. government's policy to take children away from their families and sometimes send them to the other side of the continent. And all of this led to really negative long-term consequences that we still feel today. This isn't just a history lesson. Boarding schools have created persistent, intergenerational trauma. Back to Jackie.

[00:12:06] Jackie: Because they weren't raised by their families, a lot of youth who went through boarding schools didn't have a model of what parenting should look like. So when they grew up to be adults, they had hard time parenting themselves.

They might not have been the healthiest parents. They might not have been the most present parents. It had a lot of long-term impacts on parenting. It had a lot of long-term impacts on people's mental health and their physical health. We know that when people experience Adverse Childhood Experiences that there's long-term impacts to that. It could affect your physical health. It's higher rates of diabetes, higher rates of obesity. It can impact their mental health. They're more likely to interact with the criminal justice system. All of those, I mean like many more things as well.

[00:12:56] Anne: Use substances?

[00:12:57] Jackie: Use substances. Exactly. Exactly. Substance use rates are also very, very high for people who have high ACE scores. Going to a boarding school is just a number of ACEs that add on, with an added aspect of like racism in it as well.

[00:13:16] Anne: Talk more about the aspect of racism. I mean the obvious eliminate who you are and eliminate cultures.

[00:13:24] Jackie: Yeah. So all of this was rooted in the idea, like I mentioned of kill the Indian, save the man. So the idea is that since colonization here in the United States and worldwide as well, is that people of non-European descent are lesser than. They're like lesser than human often, but they're certainly lesser than their white counterparts. So there was this idea that American Indians and Alaska Natives and other populations worldwide were savage or that they were uncivilized or that they were backwards.

And just this idea that they were not equal and that they needed to change. And that colonization was to save them and was a good thing for them. And that European people were supreme and were just more civilized and therefore were doing you a favor. So there was a racial component in the boarding schools because they wanted Native youth to be more like white people.

[00:14:31] Anne: Thinking about this intentional move to cut people off from their families, to cut people off from their culture, to try to make them into someone else. I feel like that hasn't stopped to this day, so how does that relate to behavioral health? Like why do you as a behavioral health organization work to make sure that people understand the complexities of these issues?

[00:15:02] Jackie: That's a great question. I can use myself as an example if that helps.

The reason why this kind of work is really important to me is because of my own kind of lived experiences and things that I've seen in my family, friends, my community. But talking about me specifically since it's my story and my place to tell. I grew up in a very complicated family system. And I know that we all loved each other, but there was trauma that was carried over through generations.

My parents experienced trauma from their parents and my grandparents experienced trauma from their parents. I honestly don't know how far back it goes, but I would imagine it goes back pretty far.

And I think some of it is rooted in some of the things that happen to our community and perhaps how people were treated many, many generations ago that still shows up today. And so I grew up thinking that there was something wrong with me, thinking that there was something wrong with my family and that there was something wrong with my community. Some of the challenges that I had in my own life -- I struggled with depression. I still do. And then eventually I struggled with substance use, and I thought that was because I was Native. And I thought it was because there was something wrong with my family. And I thought that it was just kind of my destiny and like it was going to happen. And it was inevitable.

[00:16:28] Anne: Just because you were Native?

[00:16:30] Jackie: Yeah, because the messages I received, I think from everybody. Everybody gave you these messages. Um, certainly when I was in school, I was a high achiever. I didn't have a lot of Native friends when I was in high school. And I would hear people say things about Natives and I'd be like, “Oh, they're not talking about me though.”

It like took until I had become an adult to really understand. It's like, well, even if they weren't talking about me, they were definitely talking about some of my cousins. Or they're definitely talking about my auntie or my uncle. So yes, they were talking about me, and I just thought I was like one of the good ones when I was in high school or something. And then I had this like crashing reality when I was on my own and an adult and trying to just deal with all these complicated things that I had experienced in life and wondering what's wrong with me. And I know that this is true for other people all over the place.

And I know that there are still people who are living in these really complicated patterns in their life because of historical trauma, because of intergenerational trauma. Who are internalizing that and thinking that there's something wrong with them or maybe thinking that there's something wrong with everybody around them. And not understanding that there's been a lot of things that have happened to us as a people, as family systems that are just really difficult to overcome. And unless you have access to resources and unless you're aware of what's going on, you're not going to be able to get the help. You're not going to, or you might not even want to. And if you think that there's something wrong with you, you're going to think there's probably something wrong with going to therapy or there's probably something wrong with going to treatment. Or there's something wrong with taking medications that can help manage your mental health.

So there's like all these really complex thought processes that go on with people. And the added like racism and stigma associated with a lot of the things we talked about, substance use, mental health, being involved in the criminal justice system, that just like all these different barriers that make people not want to access care.

So the reason why we at ANTHC decided to share the Alaska Blanket Exercise widely is because we wanted providers to understand, “Hey, your patient, isn't just not showing up or like not taking their medication because they don't want to, or because they're willfully being ignorant they're willfully being bad patients. It's because they have a lot of things going on in their lives and they're doing the best that they can to show up. And you need to understand this. You need to understand their traumas.”

It's to help Alaska Native people understand, "Hey, this is, this might be why your family is the way that they are, and there's nothing wrong with you. It's just, there's, there's been a lot that has happened." It think it just helps people be more compassionate for others and for themselves.

[00:19:33] Anne: Explain what this Blanket Exercise is.

[00:19:40] Jackie: Sure. So the Alaska Blanket Exercise is a participatory history lesson. We initially partnered with a Canadian organization called Kairos. They do a version called the Kairos Blanket Exercise in Canada. And so their exercises focused on First Nations experiences. They came to Alaska a couple of years ago and shared it with us. And the people that participated in that initial one were just so impressed with it that they wanted to bring it to Alaska.

So it is an adaptation of a Canadian exercise. The exercise itself has two parts to it. It has a history lesson and then a talking circle. For the history lesson we have people set up in a circle, a large circle of chairs around blankets. These blankets are spread out across the floor in between all the chairs, and we have participants step onto the blankets and step into the role of Alaska Native people.

When they're stepping onto the blankets, they're stepping onto traditional Alaska Native lands, which is all of Alaska. So at the beginning of the exercise, there are a lot of people on these blankets. There's a lot of blankets spread out all throughout. We also have two narrators who read through the Alaska Native history timeline.

And as they go through the timeline several things happen. The land gets smaller and the number of participants on the land, the number of Alaska Native people also gets smaller. So the things that caused the, the decrease in land or the decrease in people, are all related to actual historical events from the Alaska Native history to represent the loss of both land and people and also the relationship between Alaska Native people and the land.

Anne: And then as people go through the simulation, then what?

Jackie: So the experience itself, the history lesson portion, can be kind of intense. It's very emotional for a lot of people. We also have what we call scrolls and they're quotes from either Alaska Natives or political figures in the state of Alaska.

Some of them are really, really tough. There’s one quote in particular from a man who survived the internment camps.

[00:22:23] Anne: Jackie's talking about the internment camps for the Unangax̂ people during World War II. The US government forced the Unangax̂ to leave the Aleutians in 1942 and live in places like old fish canneries in Southeast Alaska for three years. Conditions were very, very harsh. Back to Jackie.

[00:22:42] Jackie: And he was talking about his baby brother who got double pneumonia and then died and how it was the tiniest coffin he had ever seen. The first time I did the exercise myself, I volunteered to read a quote and that's the one I got. And it was just, it was so hard to make it through and it.

That's only a small, small, small percentage of the amount of pain that family felt, that community felt for that tiny coffin. So it's a very emotional experience. I think it's especially emotional for a lot of Alaska Native participants because even if it's not directly related to an experience they had, or that one that their family might've had, they can relate to it.

There's a lot of things in there that make people think, “Oh, I wonder if that happened in my community.” So it can be quite, quite emotional. We do, I want to mention, highlight a lot of strengths in it. It’s really, truly amazing to see what people focus on. We’ve had peoples say they felt really uplifted at the end.

And that's great. Cause we try to have equal balance. Cause there have been a lot of really great things that have happened. Like Elizabeth Peratrovich, for instance, she's a great example to lift and shine, uplift and shine, or the Alaska Native Brotherhood or the Sobriety Movement. There's a lot of really great things to leave with as well. We don't try to traumatize people and then leave them. We also try to highlight a lot of the strengths and the people who are learning their culture again and who are learning their language and all of the efforts to take people are taking to combat colonization in their own personal lives or in their community.

[00:24:29] Anne: So it's both teaching about the pain so that people understand where Alaska Native communities are coming from and where we as a state are coming from, as well as highlighting that actually there's boundless resilience and boundless strength, and always has been.

[00:24:48] Jackie: Yes, absolutely. That is something that we always try to highlight is the resilience. Despite all of these things that have happened to Alaska Native people, we're still here. And we're still here in great, great numbers, and we're doing a lot of really great things in our communities and in our families. And it's important to highlight those things. It's important not to just always talk about the high rates of this or the high rates of that and this community is struggling with this. There's a lot of really great things happening in Alaska Native communities, too.

Also, another component that we didn't really touch on at all was the talking circle. So that can be another way to get people engaged in conversation. And that's part of every exercise. Our talking circle is open forum and people can talk about whatever they want or they can not talk if they don't want to.

I think that really adds to the experience. We ask that people respect each other's privacy, and not talk about it afterwards. What's talked about in the circle, stays in the circle. From our evaluations, we know that the talking circle at the end has almost as much impact on people as the actual exercise itself.

It's a time for people to kind of provide their own testimony and talk about their own experiences and for people to be vulnerable, if that's what they feel comfortable doing.

[00:26:19] Anne: I could see that being really powerful and scary experience in a lot of ways.

[00:26:27] Jackie: Absolutely.

[00:26:30] Anne: With some of the providers and behavioral health care folks that you work with, how has the Blanket Exercise changed the way they practice or the questions that they might ask to help someone along a healing process?

[00:26:50] Jackie: I think it gives people like a sense of what questions am I not asking? What information do I not have? How can I support people better? And how can I connect with them? We haven't really done any long-term outcome evaluation. That's one of the things we're really interested in doing, because we want to know how people are doing it are how people are incorporating it into their work.

But apart from just what we hear offhand, we don't have any solid answers for that yet.

[00:27:24] Anne: Jackie has big dreams for the Blanket Exercise. She wants to create versions for young people and to bring it to schools. She plans to expand the number of facilitators so that all community organizations, including private companies, can participate in the experience because it can make a difference for people who aren't involved with mental health, too. For example, she said that after managers of a grocery chain with stores in rural Alaska participated, it changed how they interacted with employees and customers. Because of COVID-19, ANTHC is currently working on creating a virtual adaptation of the Blanket Exercise. They'll start offering it for free to everyone in early 2022.

[00:28:08] Anne: What Jackie shared was only a brief piece of Alaska's history and how that history still affects Alaska communities today. It's a lot to sit with. So before we delve even deeper into ways to think about historical trauma and the effects of colonization, I'd like to invite you to take a moment to think about these issues on a more personal level and to ground yourself. If you are in a safe space to do so, maybe close your eyes, take a few deep breaths, and think about where you are and who was on this land before you. You could even consider pausing this podcast and jotting down a few thoughts, feelings, or questions that Jackie's interview brings up for you. Take a moment to reflect and then I'll introduce you to Meda.

[00:29:08] Anne: My next guest is Meda DeWitt, a traditional healer and researcher, who I asked to help me understand historical trauma more broadly and how it shapes communities.

[00:29:19] Meda: [Greeting in Tlingit is not transcribed.] My English name is Meda Witt. My Tlingit names are Tśa Tsée Naakw and Khaat kłaat, adopted Iñupiaq name is Tigigalook, and adopted Northern Cree name is Boss Eagle Spirit Woman. I live Dena’ina lands, that’s Anchorage area. I'm here with my fiancé, Chris Paoli. He and I combined have a total of eight children, seven still at home, and it's beautiful to be here.

[00:30:09] Anne: Meda is also a member of the Mental Health Mosaics Advisory Board. She says Tlingit people have a culture of wellness that stems back at least 20,000 years.